Tuesday, December 17, 2019

"Scribbling In The Sand" -- CCM and Liturgical Catechesis Pt. VI: Newsboys

Go To Pt. V

Yes, really. While the Newsboys in the last 5 years or so have receded somewhat into the background of CCM, there was a time when they were a creative force in the genre, and their music still has distinct insights to offer to the Church.

Formed in the 1980s, the Newsboys have in some ways become a legacy group. They have gained and lost members, and with the addition of Michael Tait of dcTalk as lead singer, the band has expanded its collaborative reach to more of the Christian music world.*

This post will primarily be focusing on the era prior to Tait joining the band, especially when founding member, drummer and vocalist Peter Furler was lead singer. The creative, catchy and winsome work of the Newsboys kicked into high gear when Steve Taylor (see Pt. IV of this series) entered into a creative partnership with the band, producing and co-writing numerous songs with Peter Furler, himself a highly talented lyricist, though the contributions of other founding members are not to be undervalued.

The Newsboys’ music in its heyday is distinctive for its word salad lyrics, catchy riffs, instrumental complexity and hopeful ethos. Though they did produce two worship albums, in this piece we will examine two songs which are not explicitly worship songs but do contain catechetical and liturgical elements: their hit “Shine” and the single “Entertaining Angels.”

“Shine” is loosely about evangelism, but an evangelism rooted in joy and the witness of actions as much as words. The song has a bouncing rhythm, with rapid-fire lyric verses interspersed with the chorus. “Dull as dirt/You can’t assert the kind of light/That might persuade a strict dictator to retire/Fire the army, teach the poor origami/The truth is in, the proof is when/You hear your heart/Start asking what’s my motivation,” Furler sings, subtly describing an empty evangelism common to some Christian communities which attempts to “spread the good news” without examining one’s own heart and truly living into the gospel.

By contrast, the chorus of the song, slowing down a bit, tells us to, “Shine/Make ‘em wonder what you got/Make ‘em wish that they were not/On the outside looking bored” and to “Let it shine before all men/Let ‘em see good works and then/Let ‘em glorify the Lord”. This is not merely PR. The call to “shine” is to live into the good news as if it were really good news, and the connection to good works shows that the gospel is made radiant far more by actions than by words. Indeed, the gospel is intertwined with holy action.

The second song, “Entertaining Angels,” is a slower, but still punchy love song to God, in an almost mystical way. It opens with strings, which build up to the guitar riffs. These soften slightly as Furler sings, “One to another/Do you remember me?/I feel so small/Are you listening?” The verse goes on to describe the speaker’s sense of dissatisfaction with the state of the world and the feeling of wanting to return to God. “I ran so far” evokes the Prodigal Son, and the chorus is a modern twist on both that narrative and the hospitality of Abraham:

“Entertaining angels/by the light of my TV screen/24-7, you wait for me/Entertaining angels/while the night becomes history/Hosts of Heaven, sing over me”.

To me this implies both God waiting faithfully for every human person to enter into love with Them. At the same time, there is a parallel of the human person being “host” (entertaining) to the Trinity in the every day of life (”by the light of my TV screen”). There is a deep message here that God is not remote from ourselves or from our everyday experience, but is interwoven into it even as God transfigures it. The intimacy between God and the beloved follower is elaborated on further in the second verse, where the speaker longs to be “close as a brother/The way we used to be/I’ll hold my breath/And I’ll wait for you to breathe.” This vision of true koinonia with God also blends nicely into ideals of theosis, with the implication being that God and the human person share one breath when the relationship is intimately pursued. Other devotional songs by the Newsboys expand on this theme of love and intimacy with God (cf. the song “Presence (My Heart’s Desire)”.

These two songs effectively sum up two catechetical insights from the Newsboys music. First, there is a focus on joy and engaging the wider world with love, good works and celebration of God’s goodness (a goodness which is not threatened by the good things of the world, but delights when the Kingdom breaks into everyday life). The Church would greatly benefit from the message that while the life in Christ is often a struggle, God is present in our joy as well as in our pain, and joy doesn’t have to be “churchly” to be holy. Second, their music proclaims an intimacy with the divine that does not reduce humanity to self-loathing. There is a valuable lesson that humility is not necessarily thinking less of yourself, but thinking about yourself less, and being caught up in the wonder and beauty of divine love. I am not an evangelical, but the Newsboys have a firm sense of what makes the Good News good, and it seems to me that if evangelicals want to recapture their tradition from the bad actors who have distorted it, they could do worse than to listen to some of these songs.

*Note: This post will admittedly be somewhat dunking on the Tait era. Tait is a talented singer and musician, and it’s not my intent to slam him personally. I just feel that the unique niche that the Newsboys filled in Christian music was most distinctive prior to his joining the group (in no small part due to the more active involvement of Steve Taylor and founding member Peter Furler in the songwriting process). This is not his fault.

Monday, December 16, 2019

"Scribbling in the Sand" -- CCM and Liturgical Catechesis Pt. V: Amy Grant

For this entry, I want to look at two songs. “Thy Word,” is a simple but effective and grounded worship song. “Lead Me On,” is a visionary song about liberation of various kinds.

“Thy Word” begins with the titular line from the Psalms: “Thy word is a lamp unto my feet and a light unto my path.” The musicality feels of its time, but is nonetheless compelling. Bold piano chords are interwoven with gentle synth and a soaring horn section. The chorus is a simple repetition of the Psalm line, and the verses elaborate on the speaker’s trust in God’s light and love. Though the direct Scriptural reference is from psalmody, one is also reminded distantly of 1 John 1:5: “God is light, and in Him there is no darkness at all.”

The two verses perfectly balance a recognition of human limitations and flaws with a confidence in human capacity for love and trusting in God: “I will not forget Your love for me and yet/my heart forever is wandering/Jesus be my guide and hold me to Your side/and I will love You to the end”. In contrast with some modern worship songs that place the entire impetus on God to passively save us (Bethel Music’s anthem “No Longer Slaves” comes to mind), Grant has an eye toward discipleship. The mention of love (God’s love for us and our love for God) is grounded in mutuality and true relationship. It does not let the believer off the hook for seeking to love God, but it also recognizes that that love is made possible by God’s loving care for us.

“Lead Me On” is a complex song with an unusual time signature. There is a strong echoing drum section in the back. The verses tell narratives of a people forced into hard labor and their struggle for spiritual and material freedom, and are melodically flowing with a sense of rhythmic and melodic urgency:

“ Shoulder to the wheel/For someone else’s selfish gain/Here there is no choosing/Working the clay/Wearing their anger like a ball and chain”

“Fire in the field/Underneath a blazing sun/But soon the sun was faded/And freedom was a song/I heard them singing when the day was done/Singing to the Holy One. “

The chorus climbs the scale, with lyrics of liberation that take on an eschatological bent:

“Lead me on, lead me on/To the place where the river runs into Your keeping/Lead me on, lead me on,/The awaited deliverance comforts the seeking”

One is reminded of the river of life in Revelation and other Biblical texts. This piece does emphasize the saving work of God, but also names it as a journey through “bitter cold terrain” and many struggles along the way. Yet deliverance is again ultimately on God’s initiative, as God is the “keeper” of all blessings. This also implies a deep involvement of God in creation in a way that is not deterministic, but intimate and focused on freedom.

All in all, Grant’s insights for catechesis are straightforward but profound. There is a focus on liberation which is refreshing and valuable for the Church to consider. As alluded to above with Bethel Music, freedom often gets thrown around in CCM as a concept to refer to God’s sovereignty being exercised in the life of the individual believer. By contrast, “Lead Me On” is not shy about the true evils of slavery and oppression, and seeks a freedom that is truly transformative for all God’s people in tangible ways. Eschatology blends with history in a way that refuses to erase tangible suffering and human work but which trusts that there is deliverance beyond what human action can complete.

Grant also names in “Thy Word” and other songs a focus on discipleship grounded in love. These songs remind us that while obedience to God is important, the reason for obedience is love. If we do not have affection for the God we claim to serve, it’s worth asking why, not to shame anyone for not being “devoted enough” but as a way of discerning whether our spiritual life is founded on something that is sustainable and gladdening for our own hearts and experiences. The blend of love and liberation throughout Grant’s work provides valuable lessons for the church, and these themes could easily and profoundly be expanded upon by current CCM artists who have the courage to trust that there is a God-given goodness in the human heart which can open itself to the world without losing faith in God’s transcendence.

*See Pt. I of the series

**This last track was originally written and recorded by Michael Card. Humorously, an audience member at one of Card’s concerts once asked why he played so many Amy Grant songs. He responded gently, “Because I wrote them.”

Sunday, October 20, 2019

"Scribbling in the Sand" -- CCM and Liturgical Catechesis Pt. IV: Steve Taylor

Go to Pt. III Go to Pt. V

From the 1980s to the early 1990s, Roland Stephen “Steve” Taylor emerged in the CCM scene as a unique, prophetic and rare satirical voice. Dubbed the “Clown Prince of Christian Rock”, Taylor’s work is known for its topical themes, emulation of various musical styles, and biting but insightful critique of…pretty much every meaningful target for a Christian musician to comment on. Without going into too much detail, Taylor’s work particularly towards the end of the 90s fell victim to what is known as “the satire paradox”, in which satirical media is often only properly recognized as such by people who are already aligned with the message or ideology of the satire. Many conservative Christian media curators were put off by his work, particularly when he tackled such topics as abortion. This eventually led to his disillusionment with the Christian music scene (though he remains a devout Christian and has in recent years returned to CCM as a collaboration partner). He formed the secular band “Chagall Guevara” in the 90s and eventually returned to writing Christian music when he produced songs for the Newsboys, as well as a couple of solo projects with Peter Furler once the latter left the band.

Taylor is an interesting example to talk about, because his music is very decidedly non-liturgical for the most part. He doesn’t write “worship music”, and while his world-focused commentary is in some ways similar to Petra, he is much more topical and specific. In this respect, he does actually embody I would argue one aspect of liturgy: the lifting up of the needs of the world to God and for the community to see. In a way, his music resembles an irreverent litany.

A sample of his titles should give a sense of the tone of much of his work: “Steeplechase,” “Whatever Happened to Sin,” “I Blew Up the Clinic Real Good” (his critique of militant pro-life activists), “Since I Gave Up Hope I Feel A Lot Better”.

The song I want to examine, however, is atypical of Taylor’s satirical work but falls more in line with the later work he would do producing for the Newsboys and co-writing songs with their frontman, Peter Furler. The song is a haunting, poignant piece entitled, “Harder to Believe Than Not To”.

The song opens with an achingly beautiful sample of a choral piece by Rachmaninoff. The title and concept of the song itself are taken from a letter by Flannery O’Connor in which she responds to critics who were surprised that she was a woman of faith, critics who referred to faith as a “crutch”. O’Connor responded in her letter that it was “harder to believe than not to believe.” One beauty of this song is the way it weaves in other works of art and culture in an organic way that contributes to the song’s message. In this way, Taylor offers a blueprint for building upon a kind of Holy Tradition, something that more contemporary Christian artists could stand to emulate. We all exist in a context, whether we know it or not, and Taylor draws on the talent and thought patterns of faithful Christian artists while making the song his own.

“ Nothing is colder than the winds of change/Where the chill numbs the dreamer till a shadow remains/Among the ruins lies your tortured soul/Was it lost there

Or did your will surrender control?”

The song then moves to the plaintive chorus:

“ Shivering with doubts that were left unattended

So you toss away the cloak that you should have mended

Don’t you know by now why the chosen are few?

It’s harder to believe than not to”.

This song is both a critique and an exhortation. We are encouraged to consider that the life of faith will be costly, and that discipleship is not easy. But we are also encouraged to carry on boldly and bravely, understanding that enduring and persevering through trials (without inviting them) is a sign of faithfulness, not failure (as secular society and some prosperity gospel preachers claim).

Taylor also subtly but insightfully names the forces both inside and outside the church that seek to keep us from Christ our goal:

“ Some stay paralyzed until they succumb

Others do what they feel, but their senses are numb

Some get trampled by the pious throng

Still they limp along “

Before flowing into the final chorus, Taylor offers a sly but gentle jab at those who think faith is for the weak:

“Are you sturdy enough to move to the front?

Is it nods of approval or the truth that you want?

And if they call it a crutch, then you walk with pride

Your accusers have always been afraid to go outside”

This is a laugh at the expense of the darkness, and the words of a faithful person who knows that though the battle against evil and suffering rages on, God has already won the war. It is indicative of the “upside-down Kingdom”* of God’s economy, where weakness is strength.

In this piece, Taylor offers a liturgical prayer infused with kenosis, the emptying of the self in order to receive fullness from God. Brilliantly, the song not only provides a compelling formative model for self-emptying, but also frames such kenosis as, in its own way, revolutionary. Many CCM songs talk about humbling oneself before God, but it is sadly (particularly in American evangelicalism) done in a way that equates to self-loathing. Here is a perfectly poised counterbalance to that attitude, a song which rejoices in the foolishness of the Way of Jesus in the eyes of the world while simultaneously framing faithfulness as a source of spiritual strength. Contemporary churches would do well not to shy away from the prophetic, kenotic elements in their liturgy, and to employ gifted artists and musicians who have this kind of “iconographic vision”, a vision that sees all human endeavor not in worldly terms of power, prosperity and influence, but in Kingdom terms of weakness, humility and love.

*to borrow a phrase from Donald Kraybill, Anabaptist author and theologian.

Friday, October 11, 2019

Dear Orthodox Progressives

I love you. I really do. And for the most part I love your work. Many of you have given me hope as a queer Orthodox Christian that not only is there a place for me in our tradition, but that our tradition is in fact very much about the sacrament of the human person, and the love that emerges when all of us, gay, bi, trans, and queer, live into Christ’s resurrection life. Your thoughtful, kind and luminous words rehabilitated church for me when I left the arid, rigid evangelicalism of my youth. You help me to stand strong in the face of the demagogues, the Orthodox fundamentalists, Byzantine imperialists, and all the people who seek to distort our beautiful faith in service of their own arrogance and fear of the other.

So I hope you know I appreciate you. And we need to talk about who you are, who we are, and where we’re going. We need to talk especially about the notion of respectability.

We are part of a conciliar tradition. What that means in the modern world is increasingly difficult to define, but I do feel that one of the strengths of our tradition is that we place a high value on consensus, contemplation, and harmonious accord before moving forward. This ethos has made us much more resistant* to splits and schisms, and has generally preserved a certain degree of humility among our leaders. That said, one of the things I feel we forget is that part of waiting for the Holy Spirit to “confirm” our councils and decisions as godly is that we need to step out in faith and give the Spirit something to work with. The Spirit did not tell the Apostles to stay in Jerusalem after they received the baptism by fire, but they heard the word of God to go to the ends of the Earth. We are still a part of that motion of bringing the good news to all people, and if we remain static then we are not doing our part to offer up the world for the life of the world to God.

Why am I talking about this? I’m saying it because I’m concerned that there is a tendency among Orthodox progressives to stagnate and balk at the work of faithful Christians (Orthodox and otherwise) who use more radical approaches to try and speak prophetic truth about God that we deeply need to hear. Nik Jovcic-Sas of Orthodox Provocateur carried an icon of the Theotokos with a rainbow halo gradient in a Pride parade in Belgrade, Serbia. This unsurprisingly sparked a conservative and fundamentalist backlash. More surprisingly to me, it sparked a progressive backlash. Many of you said that he was “profaning” the sacred icon by blending it with the rainbow. Some have even attacked Nik’s character and theology as being antithetical to Orthodoxy. I am troubled by our willingness to turn upon our own people. Would I have done a protest in the way Nik did? I don’t know. I’m not in touch with the Slavic Orthodox communities in the Old World. As a convert primarily running in American Greek circles, my witness to justice and inclusion will necessarily be shaped by the situation of my community. But given the long history of violence against LGBTQ+ people in Serbia and elsewhere, much of it sanctioned or even led by the Church, forgive me if I feel it’s a bit gauche to condemn someone who is clearly trying to witness to the love of Christ in a way that is very visible and frightening to the oppressive powers that be.

We may not agree with someone’s approach, but think of it this way. Radical activists are on the front lines of the fight we’re all engaged in, to make our church more clearly reflect the transformative love of the gospel. We don’t all have to be fighting on the front lines. There is much to be said for creating hospices for the wounded, for holding space within a more traditional understanding. But the forces that seek to oppress us don’t care whether we’re using their language or not. They will come for the Orthodox moderate who writes thinkpieces on re-evaluating the role of women in ministry and measured historical pieces on adelphopoiesis just as vehemently as they will attack the “Orthodox drag queen”. Look at what happened to Fr Robert Arida. Consider the backlash that Met. Kallistos Ware, a bishop, has received for what are really very mild critiques of the church’s pastoral approach to LGBTQ people.** Radicals create a space of freedom, liberation and hope we can all operate in. There are many gifts, but the same Spirit. Not all of us need to be doing what Nik is doing. But all of us need to come together and support especially those who are pushing and expanding the boundaries of what Orthodoxy can be. Those people make it safe for the rest of us to do our more introspective, thoughtful wrestling with the Truth. But if we force the radicals to conform to our ideas of what isn’t “rocking the boat”, we leave ourselves open to censure once those radicals are pushed out of the public eye. When it no longer is socially acceptable to make Pride icons or talk about the possibility of sanctity in, say, non-monogamous or non-marital relationships (for example)***, when no one will speak up for the radical, then the conservative bishops and hierarchs will begin to come down hard upon the moderate-progressive, and soon instead of the vibrant, multifaceted truth of Christ we will only have the cold voice of traditionalism, fundamentalism and idolatry.

I know my words may land harshly on some of us. I hope it’s clear that they are offered in a spirit of love, and exhortation to greater good works. We have all of us a part to play, but we need each other. I pray that we might all abide in God together, and never forget that we cannot truly make our church better unless we are willing to fight for the dignity and inclusion of all people, especially those whose ideas of church are more radical than our own.

Sincerely,

A Layman of the Eastern Church

*Though not immune, there are Orthodox splinter sects, whether we wish to acknowledge their existence or not

**This is not a call-out or a criticism of Met Kallistos’ remarks to the Wheel Journal. I really respect his willingness to speak out. I bring this up to call attention to the fact that he has suffered a disproportionate degree of backlash, and has likely avoided censorship primarily because of his high ecclesial rank. If even bishops aren’t safe, then what hope do priests or laity have if the space for prophetic critique is taken away?

***For the record, my own views on these matters are complicated. The point here is not to state an opinion one way or the other, but rather to say that these kinds of conversations can’t be silenced if we’re going to have a chance at surviving the onslaught of suppression, queerphobia, xenophobia and dead traditionalism. We may not agree with the answers that some of our siblings in Christ arrive at, but so long as they are pushing to make the Eucharistic assembly wider and more inclusive, it is imperative that we listen and come together.

Thursday, August 29, 2019

“Scribbling in the Sand” -- CCM and Liturgical Catechesis Pt. III: Petra

Go To Pt. II Go To Pt. IV

Continuing with the early days of CCM, let’s have a look at the work of a band more contemporary in style, that of Petra. A Christian rock band, Petra was formed in 1972 and continued through the 80s. Their style ranges from folkish rock to arena rock and towards the softer end of glam metal. I was introduced to the works of Petra by my parents when I was in my early teens. A part of me wonders if they wanted to offer a Christian equivalent to whatever rock and roll was popular with adolescents (though we also listened to plenty of secular music growing up). Regardless, I was impressed by their musicianship, their edge (which showed conviction without cynicism) and their thoughtful lyrics oriented towards worship, praise and developing a sense of grounded Christian identity in the modern world. Though less scholarly than Michael Card, Petra’s music still displays a prescient theological relevance for discipleship today. We will examine three songs from one of their earlier albums, More Power To Ya.

Before I get into that though, I want to mention a brief anecdote as an example of Petra’s engagement with the culture in their time. During the 1980s, a widespread “Satanic Panic” took hold in America, where many people were convinced that Satanic cults were kidnapping and abusing children. So-called “experts” on the matter claimed that rock music and other popular music had secret Satanic messages recorded into the records or tapes, which could be revealed if played backwards. Sadly, many prominent Protestant (and likely some Catholics as well) church leaders, particularly in American evangelical and fundamentalist churches, bought into this idea. On their song, “Judas’ Kiss”*, Petra recorded a deliberate backmasking message and put it at the beginning of the song so it would be clearly noticed. When played backwards, the message reads, “Why are you looking for the devil when you oughta be looking for the Lord?”, a clear playful rebuke at the church communities of their time for playing into fear rather than focusing on the love and hope in Christ.

As we did with Card, I will briefly comment on Petra’s musicality and style. Again, good liturgical catechesis and spiritual formation can be achieved with almost any style of music, but I do think that artistry is an underrated feature in CCM nowadays. While the words do the brunt of the heavy lifting to form, educate and catechize, it’s important to remember that musical effort and craft help to create a piece that will stir the soul and the heart in meaningful ways, thus allowing the words to more deeply resonate within the hearer. In Petra’s case, they were producing music similar in genre to the rock of their time, but they did it with considerable skill. Complex guitar riffs, songs that cover an impressive vocal range, careful use of synthesizers which add to the aesthetic of the piece without being distracting, these were all hallmarks of Petra’s style. Greg X Volz brought piercing, soulful vocals to the group in the early days. His replacement, John Schlitt, generally had less oomph but brought a lilting vocal style to gentler pieces and a firm, punchy vocal attack to more “hard rock” songs. Both were gifted singers and musicians who knew how to put power and emotional weight behind the songs they sang.

The first song I will examine, “Rose-Colored Stained Glass Windows,” is worth noting as a song critical of the church’s tendency to ignore uncomfortable truths and the suffering poor and retreat into self-interested worship. The song starts rather humorously with calliope music, moving into a gentle guitar solo. The indictment begins with the first lyrics, “Another sleepy Sunday safe within the walls/Outside a dying world in desperation calls”. The song gradually elevates the intensity, adding drum and more electric guitar as it reaches the chorus, “Looking through rose-colored stained glass windows/Never allowing the world to come in/Seeing no evil and feeling no pain/Making the light as it comes from within so dim”. The guitar solos beautifully build to a chorus reprise which inverts the melody up the octave.

This song is not only pointed in its rebuke, it is also particular, touching not only on general apathy but wealth and power’s ability to corrupt, “When you have so much, you think you have so much to lose/You think you have no lack, when you’re really destitute”. This is a truth that all churches need to hear, but the dominant Protestant churches in America would especially benefit from having this kind of message relayed to them. Ironically and sadly, many churches contribute to the very problem the song describes by writing worship music that fails to comment on discipleship and what we owe to one another, both those in the Church and those outside the Church. This song among others shows that spiritual music can and should challenge us as much as comfort us. “comfort the disturbed and disturb the comfortable” would be a good synecdoche for the ethos of Petra’s music.

The other song I would like to examine is the song, “Road to Zion.” This song is more devotional in nature, structured like a ballad. The instrumentation is fairly stripped down, with guitar, vocals and a small amount of keyboard. The style of the piece would, in my opinion, make it suitable for a contemporary worship service. It has verses and an easy to follow refrain. The first line evocatively describes the journey towards salvation and the fullness of life in a way that churches of all theological persuasions can relate to: “There is a Way/that leads to life/the few that find it never die/past mountain peaks graced white with snow/the way grows brighter as it goes”. This line, and indeed the entire poetic conceit of the song, stands out to me it’s fairly rare for contemporary CCM to talk about sanctification, or the process of “participating in the divine nature” (1 Peter) as we travel along the way towards becoming more fully realized and even deified human beings by grace. The influence of the evangelical model of “getting saved” in a single moment** seems to have discouraged worship music from reflecting on what Christians do after entering the life of faith, especially in such rooted metaphors. The chorus describes the life of faith as a compelling journey: “There is a road inside of you/inside of me there is one too/No stumbling pilgrim in the dark/The road to Zion’s in your heart”.

This song provides both comfort and challenge to the faithful on their journey towards Christ. It encourages the pilgrim to remember that even when we encounter shadows, “where there’s a shadow/there’s a light”. Suffering is not to be sought out, but even in the midst of it the light of Christ is present to shape and deliver us.

When “we’ve come so far, we’ve gained such ground”, the song reminds the listener to not get too comfortable, because “joy is not in where we’ve been/Joy is Who’s waiting at the end”.

To sum up, Petra is a good example of formative liturgical catechesis in a more contemporary style. As I’ve mentioned before, creating deep and formational liturgy doesn’t necessarily mean “smells and bells”. The ethos of Petra’s music brings the outside world into the Church’s memory and sphere of concern, and encourages us to see ourselves as people who are being shaped to prepare the way of the Lord.

*Which, it’s worth noting, is a song with many merits, being a sort of rock-n-roll meditation on the isolating nature of selfishness and Christ’s deep love for the lost and lonely.

**Equivalent to Baptism and/or the stage of the mystical life often called “katharsis”(purification) or “praktikos” (practice/praxis) in Orthodoxy. Also equivalent to the concept of “Justification” in Wesleyan and other Western Christian traditions

Tuesday, August 13, 2019

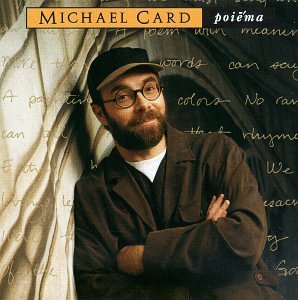

“Scribbling in the Sand” – CCM and Liturgical Catechesis Pt. II: Michael Card

Go to Pt. I Go To Pt. III

So now that I’ve established a bit of context for these reflections (see Pt. I), I’d like to begin by talking about the work of Michael Card, given that he is one of the pioneers of the CCM genre and also an exemplar of the kind of catechesis I want to talk about.*

Growing up, my parents often played his music in the car on long road trips. The first word that comes to mind thinking about my early experience of his music is the word “awe”. He was able to take the lived experience of Christian faith and make it something wondrous, lofty and awe-inspiring. As an example, I’ll use the song “The Poem of Your Life”, the title track from the above album, Poiema. The instrumentation, the rhythmic energy (drawing on Celtic styles of music as he often does) and Card’s soulful voice are all part of creating a soundscape that elevates the subject matter. This is not to say that modern worship bands can’t do this with their own style, and I don’t think there’s necessarily any one aesthetic that’s “right” or “wrong”. But if nothing else this should speak to the value of incorporating more diverse instrumentation and vocal styles into CCM, as it pushes back against the homogeneity of modern worship music, and can also create a sense of sacred time much as beautiful artistry creates a sacred space. Much of this series will be discussing lyrics and the catechetical value of the words of songs themselves, but I do think it’s important to recall that musicality matters as well.

Onto the words. There’s so much I could say, but I’ll focus in on a few lines that have, in my opinion, great didactic and formative value. First, the chorus, “the pain and the longing/the joy and the moments of light/are the rhythm and rhyme/the free verse of the poem of life”. Many modern CCM songs are either all focused on happiness or else express a well-meaning but at times shallow faith that God will triumph over all adversity. Neither of these things are bad or wrong in and of themselves, but a crucial facet of the Incarnation is that God came to share our joy and our pain, and while His will and work will ultimately triumph over evil, in the interim time God is with us in our pain but does not necessarily take it away (or at least not through supernatural or miraculous means). Card’s assertion that “the poem of life” (which God writes with us as “living letters”) contains both joy and sorrow is a humbling and encouraging call to a discipleship that does not shy away from the struggles of life. Were more Protestant churches to take this mindset seriously, perhaps they would be more willing to sit in the struggles of the oppressed and the pains of their own communities.

Card is also notable for grounding pretty much all of his songwriting in deep research and meditation on Scripture. As such, his narrative songs (of which there are many) display a groundedness in the gospel narrative that almost reminds me of the narrative sensibilities of my Orthodox Christian communities. Or, to put things in their proper chronology, my early exposure to the mystery and beauty of the gospel as a child through Card’s music was likely a major factor in my being drawn to Orthodoxy as a teenager and young adult. To illustrate this, let’s examine the song, “Stranger on the Shore,” which appears both on his album “A Fragile Stone”**, and his album on the Gospel of John, “John: A Misunderstood Messiah”. The song opens with an alliterative and highly evocative setting of the scene. The apostles are fishing after hearing the news that Jesus’ body is gone (Jn. 21), and “ In the early morning mist/They saw a Stranger on the sea shore/He some how seemed familiar/Asking what the night had brought;/With taut anticipation then/They listened to His orders/And pulling in the net, found more than they had ever caught”.

The song continues to tell the story, with Sts. Peter and John recognizing Jesus a few moments later. Moving to the chorus, Card directly invites his audience to participate in the narrative, telling us that, “You need to be confronted by the Stranger on the shore/You need to have him search your soul, you need to hear the call/You need to learn exactly what it means for you to follow/You need to understand that He’s asking for it all”. This dovetails perfectly with the final verse, where Card sings about the “painful questions that would pierce the soul of Simon,” and Jesus’ loving eyes as He gives Peter three chances to reaffirm his love in parallel to his three denials earlier. This song is an auditory icon. Like an icon, it shows us in clarity and visionary detail a narrative from the gospel. Like an icon, it is crafted with a perspective that invites the audience to enter into the story of Jesus devotionally, reverently and powerfully. The scene’s details are interwoven with the implication of the viewer into the power and purpose of the gospel. The viewer is not only moved by the pathos of the gospel scene, but is invited to a calling that is both beautiful and costly, full of love and uncertainty.

To address a practical question, it’s worth noting that narrative lyrics don’t always work in a congregational worship setting as effectively as more abstract devotional lyrics. But I do feel that Protestant churches would benefit from moments of contemplation and introspection interspersed with the congregational singing, and perhaps narrative music like this would serve well for those moments. I also feel that music is often just as effective in proclaiming the gospel as is spoken word. Like I said, these songs were really my first look into the heart of the gospel. At seminary, I have Protestant colleagues who are often very appreciative when I chant the gospel passage at our prayer gatherings, because it allows them to hear things that they might have missed before. Meditative, visionary/imaginative approaches to encountering Scripture exist in both Catholic (Ignatian prayer, lectio divina) and Orthodox (traditional iconography***, chanting of the gospel, Holy Week processions) contexts, but it seems that many low church Protestants have eschewed these approaches as “superstition”, without realizing that the gospel is much more effective when proclaimed through all the senses.

To sum up, Michael Card is committed to a Biblical and narrative approach to sacred music. He writes lovingly about both the call and cost of discipleship. He encourages his listeners to see themselves in the narrative of faith and its context. All of these things are admirable approaches to worship that any church would do well to emulate in at least some of its liturgy.

*Note: I will link to various songs throughout this series, in case people want to hear/listen to what I’m talking about

**An album dedicated to the life of St. Peter

***Not to say that Catholics don’t have iconography

So now that I’ve established a bit of context for these reflections (see Pt. I), I’d like to begin by talking about the work of Michael Card, given that he is one of the pioneers of the CCM genre and also an exemplar of the kind of catechesis I want to talk about.*

Growing up, my parents often played his music in the car on long road trips. The first word that comes to mind thinking about my early experience of his music is the word “awe”. He was able to take the lived experience of Christian faith and make it something wondrous, lofty and awe-inspiring. As an example, I’ll use the song “The Poem of Your Life”, the title track from the above album, Poiema. The instrumentation, the rhythmic energy (drawing on Celtic styles of music as he often does) and Card’s soulful voice are all part of creating a soundscape that elevates the subject matter. This is not to say that modern worship bands can’t do this with their own style, and I don’t think there’s necessarily any one aesthetic that’s “right” or “wrong”. But if nothing else this should speak to the value of incorporating more diverse instrumentation and vocal styles into CCM, as it pushes back against the homogeneity of modern worship music, and can also create a sense of sacred time much as beautiful artistry creates a sacred space. Much of this series will be discussing lyrics and the catechetical value of the words of songs themselves, but I do think it’s important to recall that musicality matters as well.

Onto the words. There’s so much I could say, but I’ll focus in on a few lines that have, in my opinion, great didactic and formative value. First, the chorus, “the pain and the longing/the joy and the moments of light/are the rhythm and rhyme/the free verse of the poem of life”. Many modern CCM songs are either all focused on happiness or else express a well-meaning but at times shallow faith that God will triumph over all adversity. Neither of these things are bad or wrong in and of themselves, but a crucial facet of the Incarnation is that God came to share our joy and our pain, and while His will and work will ultimately triumph over evil, in the interim time God is with us in our pain but does not necessarily take it away (or at least not through supernatural or miraculous means). Card’s assertion that “the poem of life” (which God writes with us as “living letters”) contains both joy and sorrow is a humbling and encouraging call to a discipleship that does not shy away from the struggles of life. Were more Protestant churches to take this mindset seriously, perhaps they would be more willing to sit in the struggles of the oppressed and the pains of their own communities.

Card is also notable for grounding pretty much all of his songwriting in deep research and meditation on Scripture. As such, his narrative songs (of which there are many) display a groundedness in the gospel narrative that almost reminds me of the narrative sensibilities of my Orthodox Christian communities. Or, to put things in their proper chronology, my early exposure to the mystery and beauty of the gospel as a child through Card’s music was likely a major factor in my being drawn to Orthodoxy as a teenager and young adult. To illustrate this, let’s examine the song, “Stranger on the Shore,” which appears both on his album “A Fragile Stone”**, and his album on the Gospel of John, “John: A Misunderstood Messiah”. The song opens with an alliterative and highly evocative setting of the scene. The apostles are fishing after hearing the news that Jesus’ body is gone (Jn. 21), and “ In the early morning mist/They saw a Stranger on the sea shore/He some how seemed familiar/Asking what the night had brought;/With taut anticipation then/They listened to His orders/And pulling in the net, found more than they had ever caught”.

The song continues to tell the story, with Sts. Peter and John recognizing Jesus a few moments later. Moving to the chorus, Card directly invites his audience to participate in the narrative, telling us that, “You need to be confronted by the Stranger on the shore/You need to have him search your soul, you need to hear the call/You need to learn exactly what it means for you to follow/You need to understand that He’s asking for it all”. This dovetails perfectly with the final verse, where Card sings about the “painful questions that would pierce the soul of Simon,” and Jesus’ loving eyes as He gives Peter three chances to reaffirm his love in parallel to his three denials earlier. This song is an auditory icon. Like an icon, it shows us in clarity and visionary detail a narrative from the gospel. Like an icon, it is crafted with a perspective that invites the audience to enter into the story of Jesus devotionally, reverently and powerfully. The scene’s details are interwoven with the implication of the viewer into the power and purpose of the gospel. The viewer is not only moved by the pathos of the gospel scene, but is invited to a calling that is both beautiful and costly, full of love and uncertainty.

To address a practical question, it’s worth noting that narrative lyrics don’t always work in a congregational worship setting as effectively as more abstract devotional lyrics. But I do feel that Protestant churches would benefit from moments of contemplation and introspection interspersed with the congregational singing, and perhaps narrative music like this would serve well for those moments. I also feel that music is often just as effective in proclaiming the gospel as is spoken word. Like I said, these songs were really my first look into the heart of the gospel. At seminary, I have Protestant colleagues who are often very appreciative when I chant the gospel passage at our prayer gatherings, because it allows them to hear things that they might have missed before. Meditative, visionary/imaginative approaches to encountering Scripture exist in both Catholic (Ignatian prayer, lectio divina) and Orthodox (traditional iconography***, chanting of the gospel, Holy Week processions) contexts, but it seems that many low church Protestants have eschewed these approaches as “superstition”, without realizing that the gospel is much more effective when proclaimed through all the senses.

To sum up, Michael Card is committed to a Biblical and narrative approach to sacred music. He writes lovingly about both the call and cost of discipleship. He encourages his listeners to see themselves in the narrative of faith and its context. All of these things are admirable approaches to worship that any church would do well to emulate in at least some of its liturgy.

*Note: I will link to various songs throughout this series, in case people want to hear/listen to what I’m talking about

**An album dedicated to the life of St. Peter

***Not to say that Catholics don’t have iconography

Saturday, August 10, 2019

“Scribbling in the Sand” -- CCM and Liturgical Catechesis -- Pt. I: Context

So…this may be a bit of a ramble, and I may end up splitting it into multiple parts. But I was listening to the music of contemporary Christian musician Michael Card (pictured above), and thinking about how while I often find myself frustrated by the lack of effort put into CCM on the radio today (and many of my Catholic and Orthodox compatriots, perhaps understandably, refuse to listen to it at all), it got me thinking about the role of music in shaping and forming people of faith in the kanon (rule) of faith.* Obviously, it’s reductive to blame the success or failure of Christian formation and discipleship in America purely on the arts, but music shapes worship and liturgy, and liturgy shapes our spiritual communities more than we realize.

Fr. Alexander Schmemann, in his seminal work, For the Life of the World, writes, “We do not need any new worship that would somehow be more adequate to our secular world. What we need is a rediscovery of the true meaning and power of worship, and this means of its cosmic, ecclesiological, and eschatological dimensions and content.”**

I would question slightly Schmemann’s assertion that there can be nothing new in worship/liturgy. I think that the Spirit has and continues to inspire gifted liturgists to compose offerings of the cosmos to God in new and powerful ways. But his point is well-taken: worship matters, especially in an age where we see an increasing de-valuing of the human person (white supremacy, homophobia, transphobia, anti-immigrant sentiment, etc). Certainly, fixing our liturgies will not miraculously solve our problems. Direct action and advocacy are needed to overcome the injustices in our society, and as surely as St. James the Just once wrote, “faith without action is dead,” Christians need to live out their faith in concrete acts of discipleship on behalf of the vulnerable in our society. But I do think that if American Christianity, and American Protestantism in particular is to “save its soul,” so to speak, part of that healing transformation will or should involve a deepening of the roots of its liturgy, worship and music to once again speak to the deep sacramentality of God’s creation and the time-honored truths of the faith.***

I and various friends of mine have agreed that, as we transitioned from churches with a low view of liturgy (ie, little emphasis on communal prayer, worship music which generated emotional intensity but often failed to teach or form people for communion with God and humanity, central focus on the personality and perspective of the preacher) to churches with a higher view of liturgy (i), we gradually became to feel that our faith and our action felt more integrated. You can no longer easily ignore, “the sick, the suffering, the captives” when you pray every Sunday for their salvation. We felt more inspired and moved to do good works, and when we did so, we felt we were doing not just a social good, but also a deeply holy thing.

As I think back to that Michael Card album, I think about some of the early CCM artists, particularly those involved with the Jesus Movement and the evangelical equivalents of the 60s counterculture and how many of them felt, at their core, like liturgists. That is to say, they wrote music not merely to produce a feeling, but to form their listeners for the life in Christ. Michael Card strikes me as exemplary of this movement. This man does so much research on Scripture and doctrine that he fills entire books with the material that doesn’t make it into his songs. In my next post, I want to focus in on Card’s work in particular, discussing how it shaped and formed my faith in a liturgical manner, and how it might continue to speak to American churches today. Through the rest of this series (yeah, pretty sure this will have to be a series now), I will examine a handful of other artists and trends in the CCM genre from the 60s-present, continuing along this theme of liturgical catechesis, how American Christian music has shaped the church, and how it might shape the church to reflect Christ more courageously against co-optation by bigotry and imperialism in the days to come.

*Greek word κανων, meaning “measuring stick,” where we get the word “canon” in the sense of “regulatory or formative work”.

** Fr. Alexander Schmemann, For the Life of the World (Crestwood, NY: St. Vladimir’s Seminary Press, 1963), 134.

***Note: a few caveats. I am speaking as an Eastern Orthodox Christian who was raised evangelical Protestant, but I will be primarily speaking about Protestant contexts in this essay, with occasional references to Orthodox theology where it sheds light on the subject. I know Protestant churches are not a monolith, and a handful of denominations seem to at least be on their way to reclaiming Christianity from the specter of whiteness, heteronormativity and patriarchy. I would cite the UCC, parts of the Episcopal Church and the ELCA as examples. I also do not write with any illusions that Orthodoxy is immune to these problems. I think we have inherited a strong, dignifying and humane liturgy but have thus far had trouble putting its meaning into practice and teaching our youth about how the Liturgy forms and shapes us. All this to say, this piece is necessarily limited in scope but I am aware of and continue to do my part to work towards resolving problems in my own spiritual community. I just feel that as someone who has experienced both liturgical “worlds”, so to speak, I am in a position to offer some thoughts that folks may find helpful.

i. Note: When I talk about “high view of liturgy” vs “low view of liturgy” I don’t necessarily mean “high church” v “low church”. There is nothing about a more contemporary style of worship that precludes having a rich liturgical life. I have been in Masses and Divine Liturgies that seemed wholly detached from their sense of purpose, and I have been in low church contexts where the sense of purpose and responsibility to offer the world up to God has been crystal clear. What I mean more is the problem of some churches who seem to have little to no sense of leitourgia as “the work of the people,” that we are coming together not just for our own edification, but to commune with God and with the world around us, through prayer, worship, teaching, formation, the sacraments/mysteries, etc.

Fr. Alexander Schmemann, in his seminal work, For the Life of the World, writes, “We do not need any new worship that would somehow be more adequate to our secular world. What we need is a rediscovery of the true meaning and power of worship, and this means of its cosmic, ecclesiological, and eschatological dimensions and content.”**

I would question slightly Schmemann’s assertion that there can be nothing new in worship/liturgy. I think that the Spirit has and continues to inspire gifted liturgists to compose offerings of the cosmos to God in new and powerful ways. But his point is well-taken: worship matters, especially in an age where we see an increasing de-valuing of the human person (white supremacy, homophobia, transphobia, anti-immigrant sentiment, etc). Certainly, fixing our liturgies will not miraculously solve our problems. Direct action and advocacy are needed to overcome the injustices in our society, and as surely as St. James the Just once wrote, “faith without action is dead,” Christians need to live out their faith in concrete acts of discipleship on behalf of the vulnerable in our society. But I do think that if American Christianity, and American Protestantism in particular is to “save its soul,” so to speak, part of that healing transformation will or should involve a deepening of the roots of its liturgy, worship and music to once again speak to the deep sacramentality of God’s creation and the time-honored truths of the faith.***

I and various friends of mine have agreed that, as we transitioned from churches with a low view of liturgy (ie, little emphasis on communal prayer, worship music which generated emotional intensity but often failed to teach or form people for communion with God and humanity, central focus on the personality and perspective of the preacher) to churches with a higher view of liturgy (i), we gradually became to feel that our faith and our action felt more integrated. You can no longer easily ignore, “the sick, the suffering, the captives” when you pray every Sunday for their salvation. We felt more inspired and moved to do good works, and when we did so, we felt we were doing not just a social good, but also a deeply holy thing.

As I think back to that Michael Card album, I think about some of the early CCM artists, particularly those involved with the Jesus Movement and the evangelical equivalents of the 60s counterculture and how many of them felt, at their core, like liturgists. That is to say, they wrote music not merely to produce a feeling, but to form their listeners for the life in Christ. Michael Card strikes me as exemplary of this movement. This man does so much research on Scripture and doctrine that he fills entire books with the material that doesn’t make it into his songs. In my next post, I want to focus in on Card’s work in particular, discussing how it shaped and formed my faith in a liturgical manner, and how it might continue to speak to American churches today. Through the rest of this series (yeah, pretty sure this will have to be a series now), I will examine a handful of other artists and trends in the CCM genre from the 60s-present, continuing along this theme of liturgical catechesis, how American Christian music has shaped the church, and how it might shape the church to reflect Christ more courageously against co-optation by bigotry and imperialism in the days to come.

*Greek word κανων, meaning “measuring stick,” where we get the word “canon” in the sense of “regulatory or formative work”.

** Fr. Alexander Schmemann, For the Life of the World (Crestwood, NY: St. Vladimir’s Seminary Press, 1963), 134.

***Note: a few caveats. I am speaking as an Eastern Orthodox Christian who was raised evangelical Protestant, but I will be primarily speaking about Protestant contexts in this essay, with occasional references to Orthodox theology where it sheds light on the subject. I know Protestant churches are not a monolith, and a handful of denominations seem to at least be on their way to reclaiming Christianity from the specter of whiteness, heteronormativity and patriarchy. I would cite the UCC, parts of the Episcopal Church and the ELCA as examples. I also do not write with any illusions that Orthodoxy is immune to these problems. I think we have inherited a strong, dignifying and humane liturgy but have thus far had trouble putting its meaning into practice and teaching our youth about how the Liturgy forms and shapes us. All this to say, this piece is necessarily limited in scope but I am aware of and continue to do my part to work towards resolving problems in my own spiritual community. I just feel that as someone who has experienced both liturgical “worlds”, so to speak, I am in a position to offer some thoughts that folks may find helpful.

i. Note: When I talk about “high view of liturgy” vs “low view of liturgy” I don’t necessarily mean “high church” v “low church”. There is nothing about a more contemporary style of worship that precludes having a rich liturgical life. I have been in Masses and Divine Liturgies that seemed wholly detached from their sense of purpose, and I have been in low church contexts where the sense of purpose and responsibility to offer the world up to God has been crystal clear. What I mean more is the problem of some churches who seem to have little to no sense of leitourgia as “the work of the people,” that we are coming together not just for our own edification, but to commune with God and with the world around us, through prayer, worship, teaching, formation, the sacraments/mysteries, etc.

“Behold the Bridegroom”: On Hard Times, Hearth Keeping and Vigil

So working my part-time job at Starbucks, I often find myself getting up before the sun. While I find the lack of sleep frustrating, after mulling over some concerns about the state of the world, the darkness this morning reminded me of a few truths of my faith. As I was getting dressed, I thought about an article I read by an environmentalist group which talked about mourning for the Earth, and the need to process our grief about climate change in order to effectively do what we can to minimize loss of life (both human and animal) in the days to come. A spine chilling line described how our task is “keeping the hearth on the far side of despair.”

How sobering, and yet also, I thought, what an honor. It reminded me of a practice in the Orthodox Church, that of keeping vigil lamps. In many parishes and in some home altars, we keep an oil lamp perpetually lit. From this lamp, we light all of our candles, whose lights remind us of the light of Christ and whose smoke reminds us of the prayers of our siblings in Christ around the world ascending to Heaven, along with the prayers of those who have gone before us in faith. At the Resurrection Vigil on Pascha night, we chant, “Come, receive the light from the Light which is never overtaken by night, and glorify Christ!”

I believe in the Resurrection, and in the hope of Christ’s life. However, in these times I often find myself looking towards the Second Coming. Maybe one symbolic resonance of the vigil lamps (albeit one not talked about often by the church) is to symbolize the Parable of the Ten Virgins (Matthew 25:1-13), some of whom were neglectful and some of whom kept their lamps burning until Christ the Bridegroom returned to carry them (and us) into the wedding feast.

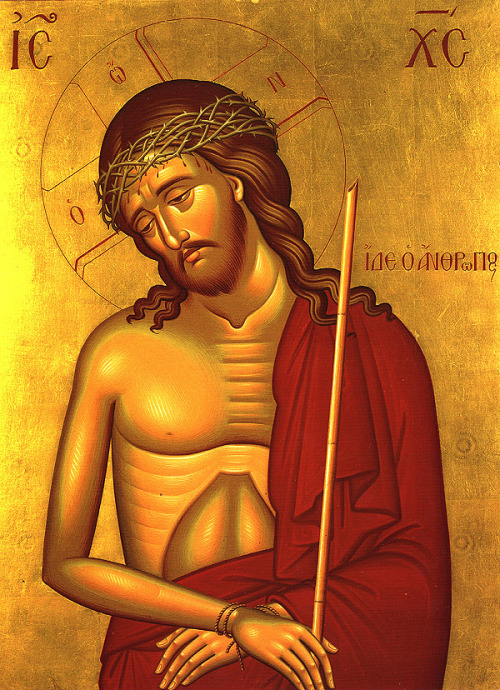

This passage and other apocalyptic images of the Kingdom of God have often been used as a kind of escapism. God will save us, so let the world burn. I don’t presume to know how the Kingdom of God will come to earth (though all evidence suggests that it *will* come to *Earth*, this making the idea of a disembodied escape to Heaven a misguided one). But I do wonder what Christ would expect of us in these trying times. Even if we cannot save the Earth in its present form, I think the vigil lamp serves as a poignant reminder that we as Christians cannot shirk our responsibilities to the cosmos, to our fellow creatures. On the Bridegroom Vespers services at the beginning of Holy Week, we display the icon of Christ the Bridegroom (above) and chant the hymn, “Behold, the Bridegroom cometh in the middle of the night, and blessed is that servant whom He shall find on watch. Unworthy the one whom He finds sleeping. Take care therefore, my soul, lest you be shut out of the Kingdom.”

With the growing sense of unrest and suffering in the world, I am pursued by the sinking feeling that “it’s later than it seems”. And it makes me think in light of our consumerist society (which I am complicit in) about what really matters. I have been pursuing a career in ministry with my canonical archdiocese. For the time being, I am staying this course, but as my seminary career continues, I am often disheartened by the ways in which I and my peers are set up for failure by our institutions. Academy, parish, workplace, etc. I’ve learned valuable things at seminary, but the workload is demanding and not always focused on depth of formation over magnitude of information being crammed into us. I love my parishes, but on a diocesan level, many lack the vision to raise up new leaders who can bring the gospel into creative witness with our times.** Rent is going up, and even as the world is at times literally burning around us, businesses care more about increasing profit and draining their workers for every last drop of cash than about caring for the laborer and providing services for those who need them. Survival, let alone thriving and pursuing our dreams, visions, and God-given vocations, is a struggle. I don’t know where my journey will lead me, but as I see my peers taking the wisdom of the ages and the Light of Christ and rebuilding the Church from the ground up, I’m beginning to feel that whatever “tending the hearth” looks like in these times, something of our old way of doing things has got to give way.

In light of our climate crisis, these words take on new meaning for me as well. So many people (myself at times included) have given in to despair and “slept” while the world bleeds. Perhaps “keeping vigil” or “keeping the hearth” means not so much standing aloof from suffering and waiting for Christ, but continually working to alleviate suffering while we anticipate His return. Perhaps the ones who will be “found sleeping” are not merely or primarily those who weren’t spending every waking moment thinking about Christ’s return*, but those who saw the suffering of God’s creation and continued to slumber. Obviously, each of us has a different capacity to help. But it seems that if the Kingdom is to come to Earth, it would behoove us to do everything we can to make sure as many of us make it to the finish line as possible. Rich and poor, young and old, needy and self-sufficient. A hearth is a place for friends and family to gather. A vigil lamp, no matter how small, pushes back the darkness. Maybe we can all keep watch together, despite our fear, and hold out for the hope that in the wedding feast of the Kingdom, God will “heal that which is infirm, and complete that which is lacking”***

*Though to do so is a valuable ascetic discipline in its own

**Whether or not I have the potential to be one of those leaders remains to be seen. I am, as the song goes, “just a beggar who gives alms”. But I can’t help but feel that many young people wanting to serve the Church and God’s people (particularly those who do not have my advantages of being cis, white and male) are kept from realizing their gifts for the benefit of the Body of Christ

***Text from the Service of Holy Orders

Saturday, July 27, 2019

The Flavor of Modern Orthodoxy: A Brief Hot Take and Rebuttal Of Met. Neophytos

So…Bishop Neophytos of Morphou, a bishop in the Orthodox Church of Cyprus, has recently been making the news for some ill-informed and frankly bizarre remarks on the origins of homosexuality. I’m not going to link to the articles in question, as I don’t feel that His Eminence needs a platform on this blog. Briefly, the bishop said that when the woman enjoys anal sex, “a desire is created, which is then transmitted to the unborn child,” (this “desire” being homosexual or bisexual orientation*). These remarks make for a good sound bite, and are, quite frankly, baffling. It’s easy to make a whole article (and many news outlets have, most of whom having only a passing knowledge of Orthodoxy) out of the debacle. However, as an Orthodox Christian myself (though not one under the Church of Cyprus), I feel compelled to…I guess contextualize the situation we’re in that leads to remarks like this, to the best of my ability, and ask the more interesting question, “Why do some modern Orthodox hierarchs seem to be stuck in this kind of thinking about contemporary social concerns?”**

Eastern Orthodoxy in the New World is very slowly being forced to grapple with the demands of modernity. A lot of people (particularly non-Orthodox Christians) are just saying “They should change with the times,” and I think that’s certainly true in the sense that we need to consider the effects some of our official doctrinal positions on social issues (prohibition on women’s ordination, same-gender marriage, not much space for trans people) and adjust them so as to better care for all of God’s children, to recognize the unique gifts of everyone to the Church, and to witness a gospel that is truly Good News. But part of Orthodoxy is an emphasis on sacred tradition, and preserving what is valuable and life-giving from the words of holy people who came before and shaped the Church to what it is today. This can be a double-edged sword, of course, but part of the reason pursuing social justice in Orthodoxy is complex is because many Orthodox churches are worried that changing means not only changing their stances on things (which many laity and some clergy are open to doing), but also “reforming” and modernizing in the way that some Protestants have, in a way that cuts them off from their history, their unique “flavor” of spirituality and witness to Christ in the wider Christian Church.

TBC, i’m not saying that being non-affirming is essential to that tradition, but the question for American Orthodoxy in particular seems to be, “Is it possible to improve our approach towards social concerns in a way that is authentic to our identity and makes use of the beauty of holy tradition, rather than making Orthodoxy into a copy of Protestant churches (not that Protestantism is bad, it’s just different)?” The American churches seem to be split between, “Yes, there probably is a way, let’s figure out how” (much of my theological reflection these days is directed towards this question, as someone who has a deep love for what is beautiful about my faith, and who also sees the flaws of its institutions and where it has failed to live out that faith in justice and mercy) and “We shouldn’t have to change, secular/non-Christian society is wrong,” which, given the memory of oppression under the Soviet regime (for Slavic Orthodox communities) the Ottoman Empire (for Greek and Middle Eastern Orthodox) and the Third Reich***, I can understand their reticence, even if I feel it is misplaced and misdirected against communities who are also now vulnerable. This sense of persecution has been ratcheted up by evangelical and fundamentalist converts to Orthodoxy (who share my background but not my experiences and convictions) who basically want to use Orthodoxy as a tool to try and put more weight behind their culture of fear and a God of wrath (not all evangelicals of course, but some). Consider Rod Dreher, or Fr. Josiah Trenham, as prime examples of this phenomenon.

Now, to finally get to the point, the Old World Orthodox churches also have the problem of grappling with modernity, but I get the sense that they are under less pressure to wrestle with these problems (though that may be changing). In Europe and to a lesser extent Asia, Orthodoxy has more cultural clout than in America because it has been a part of the culture for so long. As such, bishops and other leaders tend to be somewhat out of touch with the problems of modernity because their cultural atmosphere doesn’t force them to engage with these issues. And so many leaders, like this bishop in Cyprus, fall back on hokey pseudoscience or unexamined repetition of tradition taken out of context (most of our canon law that deals with anything resembling queerness was written for a very different time, place and context, under an empire that no longer exists), such as the remarks in this article. There are a few bishops in England and elsewhere who are doing innovative work that does wrestle with these questions, but they tend to be bishops who do not actively manage a diocese (cf. for example, Metropolitans Kallistos Ware and John Zizioulas). So…these remarks by the bishop in Cyprus are inane, but the reason why they’re persistent is more complex than just ignorance, and I think that is worth keeping in mind if we’re going to figure out how to bring the entire Christian church through the gender and sexuality debates (and other questions of adaptation to modern concerns) in a way that encourages the dignity of each church and all its people

*Metropolitan Neophytos does not mention bisexuality, nor does he mention lesbian experience, but it is my assumption that in discussing same-sex attraction, he refers to all men who love other men.

**Note: This post is my informed opinion and conjecture based on my experiences in the church. I am not an expert.

***This is to say nothing of the damage done by other Christian groups, from the Crusades to Protestant “missionary” efforts to convert the Orthodox.

Wednesday, July 3, 2019

"Giving It Back To God" -- Models of Faith in the Movie "Pilgrimage" -- Pt. VI: The Atoner

Jump to Pt. V.

CW/TW: Mentions of blood and gore

In this last entry of the series, I want to talk about the most enigmatic main character in the film, the traveling companion of the monks known only as “the Mute”. The Mute appears at the beginning of the film as a friend of the monastery, helping the monks with their daily labor but not appearing to be a formal brother himself. When Geraldus escorts the monks upon their journey, he tries to get the Mute to tell about his origins, but the Mute says nothing. Speaking on his behalf, Ciaran tells Geraldus that the Mute does not speak of his past, and that “it is not our place to question him.” Whatever the cause for his silence, the monastic community respects it as something that is the Mute’s own business, and they give him the dignity of discretion. It is made clear at various times that he can hear and understand what is being said to him.

Later, after they meet the Normans, the Mute is seen praying in the forest with his shirt off. On his back, a tattoo of a Latin cross can be seen. In the film’s language and later implications, this connects him to the Crusades, implying that he took part in them. Crusaders and pilgrims often received tattoos as a memento of their time spent in the Holy Land. The Mute, however, is keen to hide this mark of his history from others, as this is the only time he is seen with it until the end of the film when the jig is up, so to speak. Paradoxically, while the tattoo in the context of the film is a mark of potentially shameful history that the Mute wishes to leave behind, these tattoos were also used as marks of solidarity and identity by groups other than the Crusaders. During the persecutions of Coptic Christians (many of whom were likely murdered by Crusading armies), a number of Copts became tattoo artists, and would mark members of their community with a Coptic cross on the inside of the wrist. This could be visible to authorities, but it was a mark of identity and resistance to assimilation, as well as a sort of passcode for getting inside Coptic churches when they were required to hide for their own safety.* Though this may not have been intentional on the part of the filmmakers, it is worth noting that framing the Mute’s tattoo as something to be hidden except in special circumstances puts this symbol more in affinity with the underprivileged Oriental and Eastern Christian communities the Crusades victimized than with the powerful Crusaders. This is not to say that the Mute is one of these groups. He has perpetrated acts of violence against the enemies of the Crusade, and these cannot be undone. But his secrecy around this fact suggests a turn towards repentance, and a choice to undergo metanoia (a change of heart/mind) by refusing to glory in the symbol of his violence.

When the monks are attacked by brigands in the forest, the Mute first shows his unexpected battle prowess, taking out several of the monks’ attackers with swords and other weapons. Geraldus is amazed, but Diarmuid seems wary of Geraldus’ fascination with the Mute’s battle skills. The Mute goes into a kind of berserker rage when fighting, almost choking Diarmuid by accident when Diarmuid surprises him after being separated in the forest. When the Mute realizes the harm he has almost caused, he loosens his grip and bears an expression of guilt.

Raymond de Merville questions the Mute on his history multiple times, but the Mute refuses to answer.

Towards the end of the film, the surviving monks (Geraldus, Diarmuid and Cathal) are escaping the Normans with the Mute to the sea coast in order to finally set sail for Rome. Geraldus, impassioned by his fundamentalist zeal, orders the Mute to fight off the Norman enemies, promising him a place in Heaven if he does so. The Mute draws his sword and stands his ground on the beach, leaving the other monks to escape. He seems to have an awareness that this is his last act. At the same time, the resignation with which he carries himself suggests to me at least that his reason for doing so is not a desire for glory, but for penance. Having spent a long time fighting the “enemies” of God, he spent many more years living in peace with the monks. Perhaps taking a somewhat tragic interpretation of “He who lives by the sword dies by the sword” (from St. Matthew’s Gospel, Matt. 26:52), the Mute decides that he must die by the sword protecting his friends in order to finally free himself from the violence of the world which pursued him since he first took up the sword all those years ago. This leads him to the climactic final battle with Raymond de Merville, the epitome of everything the Mute has up until now renounced. Raymond desires power and glory, while the Mute has desired to live in humility and anonymity, sharing neither his name nor his story. Raymond has fought in the Crusades and wishes to shed more blood, while the Mute had fled that life when he saw the atrocity it brought upon innocents.

Raymond stabs the Mute with the torture device, leaving it embedded in the Mute’s stomach. The Mute continues fighting. Raymond, in frustration, yells out, “Tell me where you come from!” There is a long moment of silence, and then the Mute responds with his only line in the entire film: “Hell.” The Mute then bites Raymond, severing his jugular and kills him. Thus both warriors die of their wounds on the beach, and the film concludes by cutting back to the monks.

Though in some ways this exchange and scene serve the needs of Hollywood drama, I do feel that there are theological possibilities to be pondered. In the first place, it is worth noting that while violence on the whole is rightly condemned by this film, the Mute serves as an instance of the one possible exception. The Mute is the one who displays in some way the “greater love” which “has no one than this: that he lay down his life for his friends” (John 15:13). I don’t feel that this is an example of the film unequivocally condoning violence. After all, the Mute is forced into this tragic situation in part due to the violence of others. It does suggest, however, that the one avenue in which the use of force may be acceptable is in the defense of the innocent from an immediate, real threat. This is different from a holy war, and even different from “preemptive self-defense”. The monks flee until they cannot flee any longer, and the one member of their community with skill on the battlefield consents to buy them some time to escape with his own blood shed. The self-sacrificial element, though muddied in some ways by the context of war, is still present and valuable.

Finally, it’s worth noting the Mute’s final line. Again, it may have been written for the sake of drama, but it does leave interesting questions. Is the Mute a demon or an avenging angel in disguise? Does he feel forsaken to the point where he calls himself a prisoner of Hell? Is he perhaps warning Raymond of the future of Raymond’s soul as he continues down this dark path of subjugation and bloodshed? Any and all of these are possible, or perhaps another meaning entirely. Taking the last possibility as a point of inquiry though, the Mute’s clear-sightedness speaks to a facet of eschatology and soteriology which is often forgotten in more reactionary or fundamentalist Christian circles. Throughout church history (especially but not exclusively in the Christian East), divine judgment upon humanity has been seen less as a “verdict” pronounced by God arbitrarily, but more as a revelation of the state of one’s relationship to God as it already stands. In Orthodox monastic theology in particular, there is a belief that after the death of the physical body, all souls go to be in the presence of God. God is light, warmth, etc, and to those who have sought unity with God and are transfigured into divinity, this is experienced as Heaven and the communion of love with the Triune God. To those, however, who have intentionally separated themselves from God, being eternally close to God is experienced as fire, burning, and pain. Even in the Gospels, there is precedent for this, particularly in Matthew 25 and the Parable of the Sheep and the Goats. Here, what determines one’s experience is not an abstract belief in God, but one’s relationship to God as expressed through one’s actions. In the Mute, Raymond sees a mirror of himself, and the Mute uses his last words perhaps to warn Raymond that to be as he is and act as he does can only lead to an experience of Hell, not Heaven.