Thursday, August 29, 2019

“Scribbling in the Sand” -- CCM and Liturgical Catechesis Pt. III: Petra

Go To Pt. II Go To Pt. IV

Continuing with the early days of CCM, let’s have a look at the work of a band more contemporary in style, that of Petra. A Christian rock band, Petra was formed in 1972 and continued through the 80s. Their style ranges from folkish rock to arena rock and towards the softer end of glam metal. I was introduced to the works of Petra by my parents when I was in my early teens. A part of me wonders if they wanted to offer a Christian equivalent to whatever rock and roll was popular with adolescents (though we also listened to plenty of secular music growing up). Regardless, I was impressed by their musicianship, their edge (which showed conviction without cynicism) and their thoughtful lyrics oriented towards worship, praise and developing a sense of grounded Christian identity in the modern world. Though less scholarly than Michael Card, Petra’s music still displays a prescient theological relevance for discipleship today. We will examine three songs from one of their earlier albums, More Power To Ya.

Before I get into that though, I want to mention a brief anecdote as an example of Petra’s engagement with the culture in their time. During the 1980s, a widespread “Satanic Panic” took hold in America, where many people were convinced that Satanic cults were kidnapping and abusing children. So-called “experts” on the matter claimed that rock music and other popular music had secret Satanic messages recorded into the records or tapes, which could be revealed if played backwards. Sadly, many prominent Protestant (and likely some Catholics as well) church leaders, particularly in American evangelical and fundamentalist churches, bought into this idea. On their song, “Judas’ Kiss”*, Petra recorded a deliberate backmasking message and put it at the beginning of the song so it would be clearly noticed. When played backwards, the message reads, “Why are you looking for the devil when you oughta be looking for the Lord?”, a clear playful rebuke at the church communities of their time for playing into fear rather than focusing on the love and hope in Christ.

As we did with Card, I will briefly comment on Petra’s musicality and style. Again, good liturgical catechesis and spiritual formation can be achieved with almost any style of music, but I do think that artistry is an underrated feature in CCM nowadays. While the words do the brunt of the heavy lifting to form, educate and catechize, it’s important to remember that musical effort and craft help to create a piece that will stir the soul and the heart in meaningful ways, thus allowing the words to more deeply resonate within the hearer. In Petra’s case, they were producing music similar in genre to the rock of their time, but they did it with considerable skill. Complex guitar riffs, songs that cover an impressive vocal range, careful use of synthesizers which add to the aesthetic of the piece without being distracting, these were all hallmarks of Petra’s style. Greg X Volz brought piercing, soulful vocals to the group in the early days. His replacement, John Schlitt, generally had less oomph but brought a lilting vocal style to gentler pieces and a firm, punchy vocal attack to more “hard rock” songs. Both were gifted singers and musicians who knew how to put power and emotional weight behind the songs they sang.

The first song I will examine, “Rose-Colored Stained Glass Windows,” is worth noting as a song critical of the church’s tendency to ignore uncomfortable truths and the suffering poor and retreat into self-interested worship. The song starts rather humorously with calliope music, moving into a gentle guitar solo. The indictment begins with the first lyrics, “Another sleepy Sunday safe within the walls/Outside a dying world in desperation calls”. The song gradually elevates the intensity, adding drum and more electric guitar as it reaches the chorus, “Looking through rose-colored stained glass windows/Never allowing the world to come in/Seeing no evil and feeling no pain/Making the light as it comes from within so dim”. The guitar solos beautifully build to a chorus reprise which inverts the melody up the octave.

This song is not only pointed in its rebuke, it is also particular, touching not only on general apathy but wealth and power’s ability to corrupt, “When you have so much, you think you have so much to lose/You think you have no lack, when you’re really destitute”. This is a truth that all churches need to hear, but the dominant Protestant churches in America would especially benefit from having this kind of message relayed to them. Ironically and sadly, many churches contribute to the very problem the song describes by writing worship music that fails to comment on discipleship and what we owe to one another, both those in the Church and those outside the Church. This song among others shows that spiritual music can and should challenge us as much as comfort us. “comfort the disturbed and disturb the comfortable” would be a good synecdoche for the ethos of Petra’s music.

The other song I would like to examine is the song, “Road to Zion.” This song is more devotional in nature, structured like a ballad. The instrumentation is fairly stripped down, with guitar, vocals and a small amount of keyboard. The style of the piece would, in my opinion, make it suitable for a contemporary worship service. It has verses and an easy to follow refrain. The first line evocatively describes the journey towards salvation and the fullness of life in a way that churches of all theological persuasions can relate to: “There is a Way/that leads to life/the few that find it never die/past mountain peaks graced white with snow/the way grows brighter as it goes”. This line, and indeed the entire poetic conceit of the song, stands out to me it’s fairly rare for contemporary CCM to talk about sanctification, or the process of “participating in the divine nature” (1 Peter) as we travel along the way towards becoming more fully realized and even deified human beings by grace. The influence of the evangelical model of “getting saved” in a single moment** seems to have discouraged worship music from reflecting on what Christians do after entering the life of faith, especially in such rooted metaphors. The chorus describes the life of faith as a compelling journey: “There is a road inside of you/inside of me there is one too/No stumbling pilgrim in the dark/The road to Zion’s in your heart”.

This song provides both comfort and challenge to the faithful on their journey towards Christ. It encourages the pilgrim to remember that even when we encounter shadows, “where there’s a shadow/there’s a light”. Suffering is not to be sought out, but even in the midst of it the light of Christ is present to shape and deliver us.

When “we’ve come so far, we’ve gained such ground”, the song reminds the listener to not get too comfortable, because “joy is not in where we’ve been/Joy is Who’s waiting at the end”.

To sum up, Petra is a good example of formative liturgical catechesis in a more contemporary style. As I’ve mentioned before, creating deep and formational liturgy doesn’t necessarily mean “smells and bells”. The ethos of Petra’s music brings the outside world into the Church’s memory and sphere of concern, and encourages us to see ourselves as people who are being shaped to prepare the way of the Lord.

*Which, it’s worth noting, is a song with many merits, being a sort of rock-n-roll meditation on the isolating nature of selfishness and Christ’s deep love for the lost and lonely.

**Equivalent to Baptism and/or the stage of the mystical life often called “katharsis”(purification) or “praktikos” (practice/praxis) in Orthodoxy. Also equivalent to the concept of “Justification” in Wesleyan and other Western Christian traditions

Tuesday, August 13, 2019

“Scribbling in the Sand” – CCM and Liturgical Catechesis Pt. II: Michael Card

Go to Pt. I Go To Pt. III

So now that I’ve established a bit of context for these reflections (see Pt. I), I’d like to begin by talking about the work of Michael Card, given that he is one of the pioneers of the CCM genre and also an exemplar of the kind of catechesis I want to talk about.*

Growing up, my parents often played his music in the car on long road trips. The first word that comes to mind thinking about my early experience of his music is the word “awe”. He was able to take the lived experience of Christian faith and make it something wondrous, lofty and awe-inspiring. As an example, I’ll use the song “The Poem of Your Life”, the title track from the above album, Poiema. The instrumentation, the rhythmic energy (drawing on Celtic styles of music as he often does) and Card’s soulful voice are all part of creating a soundscape that elevates the subject matter. This is not to say that modern worship bands can’t do this with their own style, and I don’t think there’s necessarily any one aesthetic that’s “right” or “wrong”. But if nothing else this should speak to the value of incorporating more diverse instrumentation and vocal styles into CCM, as it pushes back against the homogeneity of modern worship music, and can also create a sense of sacred time much as beautiful artistry creates a sacred space. Much of this series will be discussing lyrics and the catechetical value of the words of songs themselves, but I do think it’s important to recall that musicality matters as well.

Onto the words. There’s so much I could say, but I’ll focus in on a few lines that have, in my opinion, great didactic and formative value. First, the chorus, “the pain and the longing/the joy and the moments of light/are the rhythm and rhyme/the free verse of the poem of life”. Many modern CCM songs are either all focused on happiness or else express a well-meaning but at times shallow faith that God will triumph over all adversity. Neither of these things are bad or wrong in and of themselves, but a crucial facet of the Incarnation is that God came to share our joy and our pain, and while His will and work will ultimately triumph over evil, in the interim time God is with us in our pain but does not necessarily take it away (or at least not through supernatural or miraculous means). Card’s assertion that “the poem of life” (which God writes with us as “living letters”) contains both joy and sorrow is a humbling and encouraging call to a discipleship that does not shy away from the struggles of life. Were more Protestant churches to take this mindset seriously, perhaps they would be more willing to sit in the struggles of the oppressed and the pains of their own communities.

Card is also notable for grounding pretty much all of his songwriting in deep research and meditation on Scripture. As such, his narrative songs (of which there are many) display a groundedness in the gospel narrative that almost reminds me of the narrative sensibilities of my Orthodox Christian communities. Or, to put things in their proper chronology, my early exposure to the mystery and beauty of the gospel as a child through Card’s music was likely a major factor in my being drawn to Orthodoxy as a teenager and young adult. To illustrate this, let’s examine the song, “Stranger on the Shore,” which appears both on his album “A Fragile Stone”**, and his album on the Gospel of John, “John: A Misunderstood Messiah”. The song opens with an alliterative and highly evocative setting of the scene. The apostles are fishing after hearing the news that Jesus’ body is gone (Jn. 21), and “ In the early morning mist/They saw a Stranger on the sea shore/He some how seemed familiar/Asking what the night had brought;/With taut anticipation then/They listened to His orders/And pulling in the net, found more than they had ever caught”.

The song continues to tell the story, with Sts. Peter and John recognizing Jesus a few moments later. Moving to the chorus, Card directly invites his audience to participate in the narrative, telling us that, “You need to be confronted by the Stranger on the shore/You need to have him search your soul, you need to hear the call/You need to learn exactly what it means for you to follow/You need to understand that He’s asking for it all”. This dovetails perfectly with the final verse, where Card sings about the “painful questions that would pierce the soul of Simon,” and Jesus’ loving eyes as He gives Peter three chances to reaffirm his love in parallel to his three denials earlier. This song is an auditory icon. Like an icon, it shows us in clarity and visionary detail a narrative from the gospel. Like an icon, it is crafted with a perspective that invites the audience to enter into the story of Jesus devotionally, reverently and powerfully. The scene’s details are interwoven with the implication of the viewer into the power and purpose of the gospel. The viewer is not only moved by the pathos of the gospel scene, but is invited to a calling that is both beautiful and costly, full of love and uncertainty.

To address a practical question, it’s worth noting that narrative lyrics don’t always work in a congregational worship setting as effectively as more abstract devotional lyrics. But I do feel that Protestant churches would benefit from moments of contemplation and introspection interspersed with the congregational singing, and perhaps narrative music like this would serve well for those moments. I also feel that music is often just as effective in proclaiming the gospel as is spoken word. Like I said, these songs were really my first look into the heart of the gospel. At seminary, I have Protestant colleagues who are often very appreciative when I chant the gospel passage at our prayer gatherings, because it allows them to hear things that they might have missed before. Meditative, visionary/imaginative approaches to encountering Scripture exist in both Catholic (Ignatian prayer, lectio divina) and Orthodox (traditional iconography***, chanting of the gospel, Holy Week processions) contexts, but it seems that many low church Protestants have eschewed these approaches as “superstition”, without realizing that the gospel is much more effective when proclaimed through all the senses.

To sum up, Michael Card is committed to a Biblical and narrative approach to sacred music. He writes lovingly about both the call and cost of discipleship. He encourages his listeners to see themselves in the narrative of faith and its context. All of these things are admirable approaches to worship that any church would do well to emulate in at least some of its liturgy.

*Note: I will link to various songs throughout this series, in case people want to hear/listen to what I’m talking about

**An album dedicated to the life of St. Peter

***Not to say that Catholics don’t have iconography

So now that I’ve established a bit of context for these reflections (see Pt. I), I’d like to begin by talking about the work of Michael Card, given that he is one of the pioneers of the CCM genre and also an exemplar of the kind of catechesis I want to talk about.*

Growing up, my parents often played his music in the car on long road trips. The first word that comes to mind thinking about my early experience of his music is the word “awe”. He was able to take the lived experience of Christian faith and make it something wondrous, lofty and awe-inspiring. As an example, I’ll use the song “The Poem of Your Life”, the title track from the above album, Poiema. The instrumentation, the rhythmic energy (drawing on Celtic styles of music as he often does) and Card’s soulful voice are all part of creating a soundscape that elevates the subject matter. This is not to say that modern worship bands can’t do this with their own style, and I don’t think there’s necessarily any one aesthetic that’s “right” or “wrong”. But if nothing else this should speak to the value of incorporating more diverse instrumentation and vocal styles into CCM, as it pushes back against the homogeneity of modern worship music, and can also create a sense of sacred time much as beautiful artistry creates a sacred space. Much of this series will be discussing lyrics and the catechetical value of the words of songs themselves, but I do think it’s important to recall that musicality matters as well.

Onto the words. There’s so much I could say, but I’ll focus in on a few lines that have, in my opinion, great didactic and formative value. First, the chorus, “the pain and the longing/the joy and the moments of light/are the rhythm and rhyme/the free verse of the poem of life”. Many modern CCM songs are either all focused on happiness or else express a well-meaning but at times shallow faith that God will triumph over all adversity. Neither of these things are bad or wrong in and of themselves, but a crucial facet of the Incarnation is that God came to share our joy and our pain, and while His will and work will ultimately triumph over evil, in the interim time God is with us in our pain but does not necessarily take it away (or at least not through supernatural or miraculous means). Card’s assertion that “the poem of life” (which God writes with us as “living letters”) contains both joy and sorrow is a humbling and encouraging call to a discipleship that does not shy away from the struggles of life. Were more Protestant churches to take this mindset seriously, perhaps they would be more willing to sit in the struggles of the oppressed and the pains of their own communities.

Card is also notable for grounding pretty much all of his songwriting in deep research and meditation on Scripture. As such, his narrative songs (of which there are many) display a groundedness in the gospel narrative that almost reminds me of the narrative sensibilities of my Orthodox Christian communities. Or, to put things in their proper chronology, my early exposure to the mystery and beauty of the gospel as a child through Card’s music was likely a major factor in my being drawn to Orthodoxy as a teenager and young adult. To illustrate this, let’s examine the song, “Stranger on the Shore,” which appears both on his album “A Fragile Stone”**, and his album on the Gospel of John, “John: A Misunderstood Messiah”. The song opens with an alliterative and highly evocative setting of the scene. The apostles are fishing after hearing the news that Jesus’ body is gone (Jn. 21), and “ In the early morning mist/They saw a Stranger on the sea shore/He some how seemed familiar/Asking what the night had brought;/With taut anticipation then/They listened to His orders/And pulling in the net, found more than they had ever caught”.

The song continues to tell the story, with Sts. Peter and John recognizing Jesus a few moments later. Moving to the chorus, Card directly invites his audience to participate in the narrative, telling us that, “You need to be confronted by the Stranger on the shore/You need to have him search your soul, you need to hear the call/You need to learn exactly what it means for you to follow/You need to understand that He’s asking for it all”. This dovetails perfectly with the final verse, where Card sings about the “painful questions that would pierce the soul of Simon,” and Jesus’ loving eyes as He gives Peter three chances to reaffirm his love in parallel to his three denials earlier. This song is an auditory icon. Like an icon, it shows us in clarity and visionary detail a narrative from the gospel. Like an icon, it is crafted with a perspective that invites the audience to enter into the story of Jesus devotionally, reverently and powerfully. The scene’s details are interwoven with the implication of the viewer into the power and purpose of the gospel. The viewer is not only moved by the pathos of the gospel scene, but is invited to a calling that is both beautiful and costly, full of love and uncertainty.

To address a practical question, it’s worth noting that narrative lyrics don’t always work in a congregational worship setting as effectively as more abstract devotional lyrics. But I do feel that Protestant churches would benefit from moments of contemplation and introspection interspersed with the congregational singing, and perhaps narrative music like this would serve well for those moments. I also feel that music is often just as effective in proclaiming the gospel as is spoken word. Like I said, these songs were really my first look into the heart of the gospel. At seminary, I have Protestant colleagues who are often very appreciative when I chant the gospel passage at our prayer gatherings, because it allows them to hear things that they might have missed before. Meditative, visionary/imaginative approaches to encountering Scripture exist in both Catholic (Ignatian prayer, lectio divina) and Orthodox (traditional iconography***, chanting of the gospel, Holy Week processions) contexts, but it seems that many low church Protestants have eschewed these approaches as “superstition”, without realizing that the gospel is much more effective when proclaimed through all the senses.

To sum up, Michael Card is committed to a Biblical and narrative approach to sacred music. He writes lovingly about both the call and cost of discipleship. He encourages his listeners to see themselves in the narrative of faith and its context. All of these things are admirable approaches to worship that any church would do well to emulate in at least some of its liturgy.

*Note: I will link to various songs throughout this series, in case people want to hear/listen to what I’m talking about

**An album dedicated to the life of St. Peter

***Not to say that Catholics don’t have iconography

Saturday, August 10, 2019

“Scribbling in the Sand” -- CCM and Liturgical Catechesis -- Pt. I: Context

So…this may be a bit of a ramble, and I may end up splitting it into multiple parts. But I was listening to the music of contemporary Christian musician Michael Card (pictured above), and thinking about how while I often find myself frustrated by the lack of effort put into CCM on the radio today (and many of my Catholic and Orthodox compatriots, perhaps understandably, refuse to listen to it at all), it got me thinking about the role of music in shaping and forming people of faith in the kanon (rule) of faith.* Obviously, it’s reductive to blame the success or failure of Christian formation and discipleship in America purely on the arts, but music shapes worship and liturgy, and liturgy shapes our spiritual communities more than we realize.

Fr. Alexander Schmemann, in his seminal work, For the Life of the World, writes, “We do not need any new worship that would somehow be more adequate to our secular world. What we need is a rediscovery of the true meaning and power of worship, and this means of its cosmic, ecclesiological, and eschatological dimensions and content.”**

I would question slightly Schmemann’s assertion that there can be nothing new in worship/liturgy. I think that the Spirit has and continues to inspire gifted liturgists to compose offerings of the cosmos to God in new and powerful ways. But his point is well-taken: worship matters, especially in an age where we see an increasing de-valuing of the human person (white supremacy, homophobia, transphobia, anti-immigrant sentiment, etc). Certainly, fixing our liturgies will not miraculously solve our problems. Direct action and advocacy are needed to overcome the injustices in our society, and as surely as St. James the Just once wrote, “faith without action is dead,” Christians need to live out their faith in concrete acts of discipleship on behalf of the vulnerable in our society. But I do think that if American Christianity, and American Protestantism in particular is to “save its soul,” so to speak, part of that healing transformation will or should involve a deepening of the roots of its liturgy, worship and music to once again speak to the deep sacramentality of God’s creation and the time-honored truths of the faith.***

I and various friends of mine have agreed that, as we transitioned from churches with a low view of liturgy (ie, little emphasis on communal prayer, worship music which generated emotional intensity but often failed to teach or form people for communion with God and humanity, central focus on the personality and perspective of the preacher) to churches with a higher view of liturgy (i), we gradually became to feel that our faith and our action felt more integrated. You can no longer easily ignore, “the sick, the suffering, the captives” when you pray every Sunday for their salvation. We felt more inspired and moved to do good works, and when we did so, we felt we were doing not just a social good, but also a deeply holy thing.

As I think back to that Michael Card album, I think about some of the early CCM artists, particularly those involved with the Jesus Movement and the evangelical equivalents of the 60s counterculture and how many of them felt, at their core, like liturgists. That is to say, they wrote music not merely to produce a feeling, but to form their listeners for the life in Christ. Michael Card strikes me as exemplary of this movement. This man does so much research on Scripture and doctrine that he fills entire books with the material that doesn’t make it into his songs. In my next post, I want to focus in on Card’s work in particular, discussing how it shaped and formed my faith in a liturgical manner, and how it might continue to speak to American churches today. Through the rest of this series (yeah, pretty sure this will have to be a series now), I will examine a handful of other artists and trends in the CCM genre from the 60s-present, continuing along this theme of liturgical catechesis, how American Christian music has shaped the church, and how it might shape the church to reflect Christ more courageously against co-optation by bigotry and imperialism in the days to come.

*Greek word κανων, meaning “measuring stick,” where we get the word “canon” in the sense of “regulatory or formative work”.

** Fr. Alexander Schmemann, For the Life of the World (Crestwood, NY: St. Vladimir’s Seminary Press, 1963), 134.

***Note: a few caveats. I am speaking as an Eastern Orthodox Christian who was raised evangelical Protestant, but I will be primarily speaking about Protestant contexts in this essay, with occasional references to Orthodox theology where it sheds light on the subject. I know Protestant churches are not a monolith, and a handful of denominations seem to at least be on their way to reclaiming Christianity from the specter of whiteness, heteronormativity and patriarchy. I would cite the UCC, parts of the Episcopal Church and the ELCA as examples. I also do not write with any illusions that Orthodoxy is immune to these problems. I think we have inherited a strong, dignifying and humane liturgy but have thus far had trouble putting its meaning into practice and teaching our youth about how the Liturgy forms and shapes us. All this to say, this piece is necessarily limited in scope but I am aware of and continue to do my part to work towards resolving problems in my own spiritual community. I just feel that as someone who has experienced both liturgical “worlds”, so to speak, I am in a position to offer some thoughts that folks may find helpful.

i. Note: When I talk about “high view of liturgy” vs “low view of liturgy” I don’t necessarily mean “high church” v “low church”. There is nothing about a more contemporary style of worship that precludes having a rich liturgical life. I have been in Masses and Divine Liturgies that seemed wholly detached from their sense of purpose, and I have been in low church contexts where the sense of purpose and responsibility to offer the world up to God has been crystal clear. What I mean more is the problem of some churches who seem to have little to no sense of leitourgia as “the work of the people,” that we are coming together not just for our own edification, but to commune with God and with the world around us, through prayer, worship, teaching, formation, the sacraments/mysteries, etc.

Fr. Alexander Schmemann, in his seminal work, For the Life of the World, writes, “We do not need any new worship that would somehow be more adequate to our secular world. What we need is a rediscovery of the true meaning and power of worship, and this means of its cosmic, ecclesiological, and eschatological dimensions and content.”**

I would question slightly Schmemann’s assertion that there can be nothing new in worship/liturgy. I think that the Spirit has and continues to inspire gifted liturgists to compose offerings of the cosmos to God in new and powerful ways. But his point is well-taken: worship matters, especially in an age where we see an increasing de-valuing of the human person (white supremacy, homophobia, transphobia, anti-immigrant sentiment, etc). Certainly, fixing our liturgies will not miraculously solve our problems. Direct action and advocacy are needed to overcome the injustices in our society, and as surely as St. James the Just once wrote, “faith without action is dead,” Christians need to live out their faith in concrete acts of discipleship on behalf of the vulnerable in our society. But I do think that if American Christianity, and American Protestantism in particular is to “save its soul,” so to speak, part of that healing transformation will or should involve a deepening of the roots of its liturgy, worship and music to once again speak to the deep sacramentality of God’s creation and the time-honored truths of the faith.***

I and various friends of mine have agreed that, as we transitioned from churches with a low view of liturgy (ie, little emphasis on communal prayer, worship music which generated emotional intensity but often failed to teach or form people for communion with God and humanity, central focus on the personality and perspective of the preacher) to churches with a higher view of liturgy (i), we gradually became to feel that our faith and our action felt more integrated. You can no longer easily ignore, “the sick, the suffering, the captives” when you pray every Sunday for their salvation. We felt more inspired and moved to do good works, and when we did so, we felt we were doing not just a social good, but also a deeply holy thing.

As I think back to that Michael Card album, I think about some of the early CCM artists, particularly those involved with the Jesus Movement and the evangelical equivalents of the 60s counterculture and how many of them felt, at their core, like liturgists. That is to say, they wrote music not merely to produce a feeling, but to form their listeners for the life in Christ. Michael Card strikes me as exemplary of this movement. This man does so much research on Scripture and doctrine that he fills entire books with the material that doesn’t make it into his songs. In my next post, I want to focus in on Card’s work in particular, discussing how it shaped and formed my faith in a liturgical manner, and how it might continue to speak to American churches today. Through the rest of this series (yeah, pretty sure this will have to be a series now), I will examine a handful of other artists and trends in the CCM genre from the 60s-present, continuing along this theme of liturgical catechesis, how American Christian music has shaped the church, and how it might shape the church to reflect Christ more courageously against co-optation by bigotry and imperialism in the days to come.

*Greek word κανων, meaning “measuring stick,” where we get the word “canon” in the sense of “regulatory or formative work”.

** Fr. Alexander Schmemann, For the Life of the World (Crestwood, NY: St. Vladimir’s Seminary Press, 1963), 134.

***Note: a few caveats. I am speaking as an Eastern Orthodox Christian who was raised evangelical Protestant, but I will be primarily speaking about Protestant contexts in this essay, with occasional references to Orthodox theology where it sheds light on the subject. I know Protestant churches are not a monolith, and a handful of denominations seem to at least be on their way to reclaiming Christianity from the specter of whiteness, heteronormativity and patriarchy. I would cite the UCC, parts of the Episcopal Church and the ELCA as examples. I also do not write with any illusions that Orthodoxy is immune to these problems. I think we have inherited a strong, dignifying and humane liturgy but have thus far had trouble putting its meaning into practice and teaching our youth about how the Liturgy forms and shapes us. All this to say, this piece is necessarily limited in scope but I am aware of and continue to do my part to work towards resolving problems in my own spiritual community. I just feel that as someone who has experienced both liturgical “worlds”, so to speak, I am in a position to offer some thoughts that folks may find helpful.

i. Note: When I talk about “high view of liturgy” vs “low view of liturgy” I don’t necessarily mean “high church” v “low church”. There is nothing about a more contemporary style of worship that precludes having a rich liturgical life. I have been in Masses and Divine Liturgies that seemed wholly detached from their sense of purpose, and I have been in low church contexts where the sense of purpose and responsibility to offer the world up to God has been crystal clear. What I mean more is the problem of some churches who seem to have little to no sense of leitourgia as “the work of the people,” that we are coming together not just for our own edification, but to commune with God and with the world around us, through prayer, worship, teaching, formation, the sacraments/mysteries, etc.

“Behold the Bridegroom”: On Hard Times, Hearth Keeping and Vigil

So working my part-time job at Starbucks, I often find myself getting up before the sun. While I find the lack of sleep frustrating, after mulling over some concerns about the state of the world, the darkness this morning reminded me of a few truths of my faith. As I was getting dressed, I thought about an article I read by an environmentalist group which talked about mourning for the Earth, and the need to process our grief about climate change in order to effectively do what we can to minimize loss of life (both human and animal) in the days to come. A spine chilling line described how our task is “keeping the hearth on the far side of despair.”

How sobering, and yet also, I thought, what an honor. It reminded me of a practice in the Orthodox Church, that of keeping vigil lamps. In many parishes and in some home altars, we keep an oil lamp perpetually lit. From this lamp, we light all of our candles, whose lights remind us of the light of Christ and whose smoke reminds us of the prayers of our siblings in Christ around the world ascending to Heaven, along with the prayers of those who have gone before us in faith. At the Resurrection Vigil on Pascha night, we chant, “Come, receive the light from the Light which is never overtaken by night, and glorify Christ!”

I believe in the Resurrection, and in the hope of Christ’s life. However, in these times I often find myself looking towards the Second Coming. Maybe one symbolic resonance of the vigil lamps (albeit one not talked about often by the church) is to symbolize the Parable of the Ten Virgins (Matthew 25:1-13), some of whom were neglectful and some of whom kept their lamps burning until Christ the Bridegroom returned to carry them (and us) into the wedding feast.

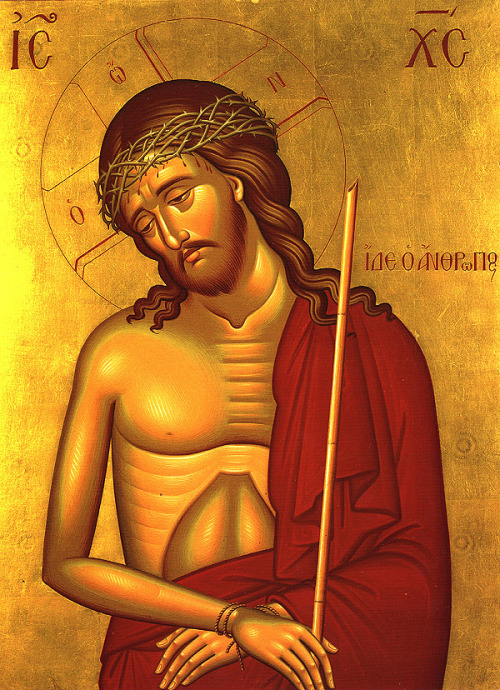

This passage and other apocalyptic images of the Kingdom of God have often been used as a kind of escapism. God will save us, so let the world burn. I don’t presume to know how the Kingdom of God will come to earth (though all evidence suggests that it *will* come to *Earth*, this making the idea of a disembodied escape to Heaven a misguided one). But I do wonder what Christ would expect of us in these trying times. Even if we cannot save the Earth in its present form, I think the vigil lamp serves as a poignant reminder that we as Christians cannot shirk our responsibilities to the cosmos, to our fellow creatures. On the Bridegroom Vespers services at the beginning of Holy Week, we display the icon of Christ the Bridegroom (above) and chant the hymn, “Behold, the Bridegroom cometh in the middle of the night, and blessed is that servant whom He shall find on watch. Unworthy the one whom He finds sleeping. Take care therefore, my soul, lest you be shut out of the Kingdom.”

With the growing sense of unrest and suffering in the world, I am pursued by the sinking feeling that “it’s later than it seems”. And it makes me think in light of our consumerist society (which I am complicit in) about what really matters. I have been pursuing a career in ministry with my canonical archdiocese. For the time being, I am staying this course, but as my seminary career continues, I am often disheartened by the ways in which I and my peers are set up for failure by our institutions. Academy, parish, workplace, etc. I’ve learned valuable things at seminary, but the workload is demanding and not always focused on depth of formation over magnitude of information being crammed into us. I love my parishes, but on a diocesan level, many lack the vision to raise up new leaders who can bring the gospel into creative witness with our times.** Rent is going up, and even as the world is at times literally burning around us, businesses care more about increasing profit and draining their workers for every last drop of cash than about caring for the laborer and providing services for those who need them. Survival, let alone thriving and pursuing our dreams, visions, and God-given vocations, is a struggle. I don’t know where my journey will lead me, but as I see my peers taking the wisdom of the ages and the Light of Christ and rebuilding the Church from the ground up, I’m beginning to feel that whatever “tending the hearth” looks like in these times, something of our old way of doing things has got to give way.

In light of our climate crisis, these words take on new meaning for me as well. So many people (myself at times included) have given in to despair and “slept” while the world bleeds. Perhaps “keeping vigil” or “keeping the hearth” means not so much standing aloof from suffering and waiting for Christ, but continually working to alleviate suffering while we anticipate His return. Perhaps the ones who will be “found sleeping” are not merely or primarily those who weren’t spending every waking moment thinking about Christ’s return*, but those who saw the suffering of God’s creation and continued to slumber. Obviously, each of us has a different capacity to help. But it seems that if the Kingdom is to come to Earth, it would behoove us to do everything we can to make sure as many of us make it to the finish line as possible. Rich and poor, young and old, needy and self-sufficient. A hearth is a place for friends and family to gather. A vigil lamp, no matter how small, pushes back the darkness. Maybe we can all keep watch together, despite our fear, and hold out for the hope that in the wedding feast of the Kingdom, God will “heal that which is infirm, and complete that which is lacking”***

*Though to do so is a valuable ascetic discipline in its own

**Whether or not I have the potential to be one of those leaders remains to be seen. I am, as the song goes, “just a beggar who gives alms”. But I can’t help but feel that many young people wanting to serve the Church and God’s people (particularly those who do not have my advantages of being cis, white and male) are kept from realizing their gifts for the benefit of the Body of Christ

***Text from the Service of Holy Orders

Subscribe to:

Comments (Atom)