The Beats, Religious De/Re-Construction, and the Politics of Pathos

(An Autobiographical Ramble)

Trigger Warning: The following post rogram contains frank though non graphic discussion of sex, homophobia, queerphobia, racism, and pedophilia. I will warn y’all when we get to the really gnarly bits, but reader discretion is advised

A lot of my fellow Christian and Christian adjacent folks, particularly those of us in the queer community, are in the process of deconstructing their relationship to the conservative Christianities they were brought up to believe in. Some end up reconstructing something new within a Christian paradigm, and some end up finding another religious faith or deciding religion simply isn’t for them. As I’ve reflected on this trend, I realize that my story is different than many of my peers. Not better or worse, just different. And I want to talk about it. I’m realizing more and more that my approach to becoming a fully self-realized queer Christian spiritual worker was mediated by my journey through the Beats. For those who aren’t familiar, the Beats or Beat movement were a group of artists and writers in the 1940s and 50s who served as one of the countercultural voices prefiguring the hippie movements of the 1960s.There are many common threads I could trace in my journey, but almost all of them touch on the Beats, both the Beat canon and the Beat ways of understanding the world and my place in it. At a time when exvangelical wasn’t really a thing, I couldn’t exactly look to contemporary voices on my journey of self-discovery. Instead I looked back to stranger voices, mediated by kind mentors who were either survivors of that time or were kin to those who were. Let me tell you a story.

I. “Forbidden” Fruit

Growing up near Boulder, I was exposed to New Age culture and spirituality by osmosis. New Age was seen by my conservative church as a spiritual symptom of the non-Christian world’s depravity. Even as a kid, I don’t know how much I agreed with this ideology. I definitely found New Age spirituality foreign and unsettling at times, and for that reason I definitely judged it by the rhetoric I was taught. But if you had asked me what was “wrong” with it, other than an appeal to monotheism over polytheism, I’m not sure I could have told you. What I think I’m trying to say is that it also had a kind of fascination for me. Perhaps it was the forbidden fruit, but there was also a sensuality and a beauty to much of its imagery which was not reflected in my stoic Reformed evangelical upbringing (except perhaps in a few spiritual retreats).

I will here somewhat use New Age ideas and the hippie movement as a bridge to talking about the Beats, even though the two movements were distinct in their own ways.

Somewhere lost in the mists of time and my consciousness was a point of disaffection with the evangelical Christianity I was raised in. Somehow, even at age 14, I began to ask some of the questions that many of my peers would not ask until high school or college. I think some of this was rooted in the disconnect I felt between the very personal, earthy evangelicalism of my church’s youth group and the abstract, austere evangelicalism of what was preached on Sundays. In search of my own becoming, and in search of a spirituality more like what my friends and I were beginning to learn and practice, a spirituality that made the gospel story come alive, I paradoxically began to look outside of Christianity.

Around this time, I read Huston Smith’s “The World’s Religions”. A quick Google search reveals that Huston Smith was active in the counterculture of the 1960s and was influenced by Timothy Leary and others who were themselves influenced by the Beats. Though Smith’s book is by no means partial, there was a kind of sensibility which got at the spiritual ethos and yearnings of different world religions in a way that flat prose about their beliefs and practices did not. I detect now in his work the same kind of curiosity about the human spirit that motivated the Beats. His accounts of Buddhism and Raja yoga were the first accounts that were compelling enough for me to try those traditions as solutions to my existential angst with Christianity. They did not resolve my desire for intimate relationship with the God of Abraham, Isaac, Jacob and the Apostles, but they did teach me valuable practices of contemplation, which helped me to ground the faith I had been cultivating in a sensibility of discovery and practice, rather than the austere passivity I had been taught.

In middle and high school, I had a few teachers who served as personal mentors to me. One, my science teacher, had herself lived through the anti-war movements of the 60s and 70s that the Beats had culturally been predecessors to, along with other more “on the ground” activists. She taught us how to think rather than what to think, and she would often go on long, inspired tangents about the power of human creativity, curiosity, and love to change the world. After these tangents, she would always half-jokingly apologize, asking us to tell her when she got off track. We never did, because these long dialogues were profoundly meaningful to us.

In high school, my social studies teacher was a blacksmith, historian and storyteller. I worked long hours in his metal forge at an apprenticeship, and he taught me how to better understand the historical component of the beliefs and worldviews that shape us as human beings. He also instilled in me a love of myth for its archetypal value. He gave me books from the New Wave science fiction movement of the 50s-70s, a movement which gave technology a back seat role to the exploration of consciousness, community, belonging, and “inner space” just as early sci fi had focused on “outer space”. There was an anarchic streak running through these writers, just as there had been in the Beats before them. Sex, drugs, and rock and roll, but also long meandering discourses on the meaning of life, the limits of human capacity, and our reaching for something like wholeness.

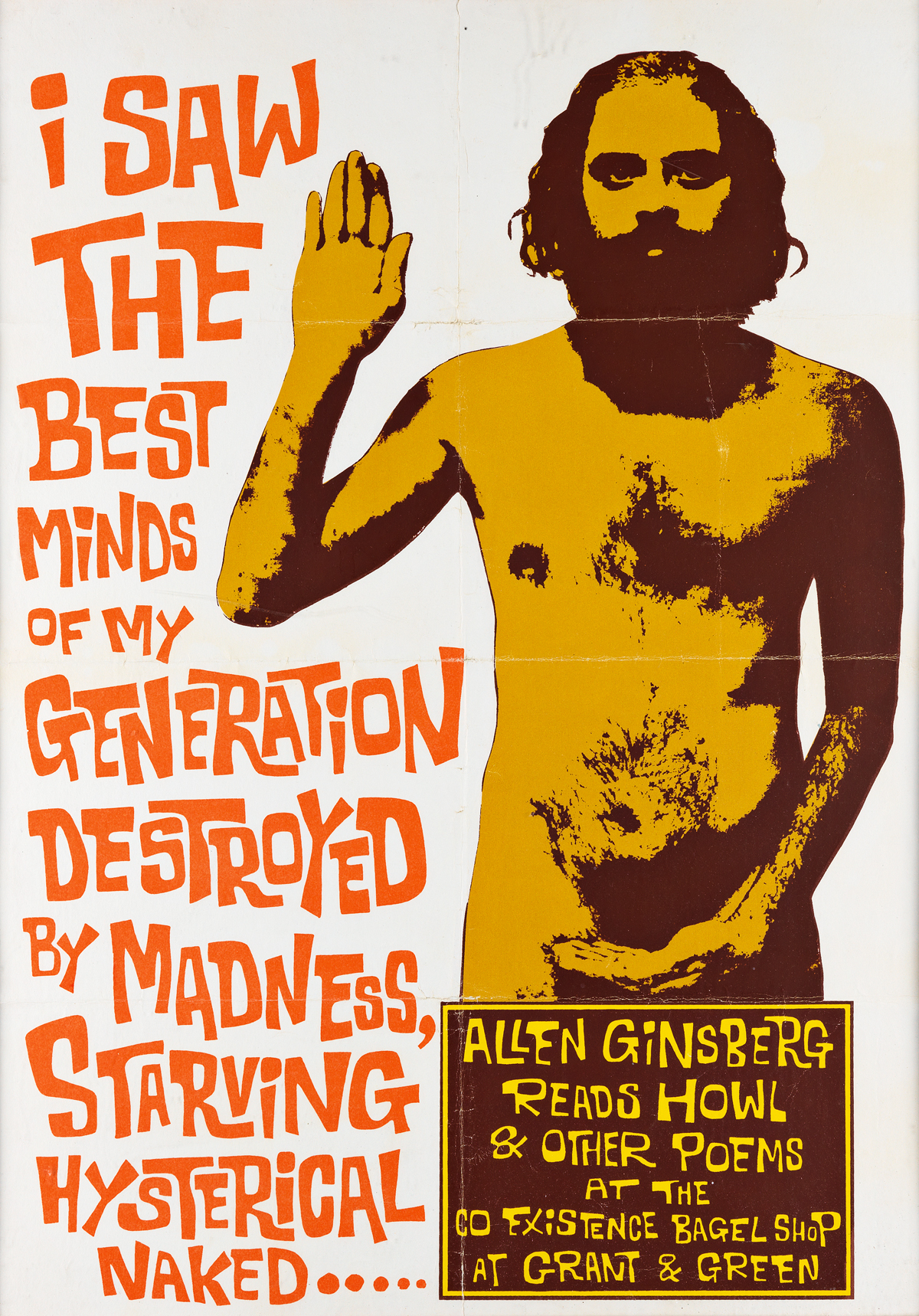

II. Queer Lightning - Ginsberg’s “Howl”

In 8th grade English class, I was exposed to Allen Ginsberg’s seminal poem, Howl, and it shattered my preconceived notions of what poetry could be. Even as a beginning free verse poet myself, the sheer anguish, lyricism, improvisational freedom and intensity of “Howl” shook me up in all the right ways. I wouldn’t have had words for it at the time, but Ginsberg’s voice screamed from the rooftops about the kind of alienation and self-fragmentation I could only whisper about to myself in my own heart as a vague sense of dread. I could not relate to the material conditions Ginsberg found himself and his beloveds in, but I could relate to the deep loneliness, anger and yearning he expressed as a lover trying to survive in a totalizing world of capitalist white supremacist patriarchy. That feeling of relation/identification was more than teenage melodrama. I think the alienation many especially white adolescents face is a symptom of the deeper social “madness” caused by oppressive systems which Ginsberg alluded to in his poem. For me personally, “Howl” was an emotional grasping at realities and knowledges that entangled and banged against each other in my psyche and my body.

The homoerotic current in Howl was not one I necessarily had conscious opinions on at the time, but I don’t doubt that it was one that my body and my eros responded to. As a boy myself only just beginning to realize his love and yearning for other boys, Ginsberg’s explicit references to male sexuality and his more tender homosocial and homoerotic lines to Carl Solomon cascaded through my subconscious like a flash of queer lightning. It pointed to something far vaster and stranger in my own desire, something that Ginsberg had and something that I felt a kind of similarity and solidarity with.

In terms of sexuality, the homoerotic elements of the Beats continued to influence me in unconscious ways, and their frank treatment of sexuality and sexual hedonism was, I think, an unrecognized lifeline for me. Purity culture, though far less violent on men than women, had mostly succeeded in cutting me off from my own desire. I feel that my internalization of its norms created a split within me. This split caused me to project my romantic and relational desires onto my attraction to women and my sexuality onto my attraction to men. I then subconsciously framed my sexuality as a target for repression. But The Beats kept me honest in spite of myself, and even if I internalized sexual repression, their sexual liberation was part of what kept me from buying into purity culture as a moral good. I remember in particular being deeply moved by passages in from Beat poet Michael McClure’s “Fuck Ode,” an earthy, graphic depiction of sex in stream-of-consciousness poetry not dissimilar to a modern day Song of Songs.

The blend of sexuality, spirituality and even references to drug use created for me a kind of breathing space. As an adolescent still struggling to even know what I wanted out of my life and love, here were creatives and spiritualists who radically expanded my notions of what it was possible to want. I knew that while I didn’t aspire to the level of hedonism or rebellion they embodied, the fact that they lived out such a wild life proved that whatever I personally aspired to was possible without extinction. That whatever I wanted to do or be, it was never going to be quite as radical as these creatives I admired, so I may as well begin to push the limits of my own desire and becoming.

III. (Beat)itude

At age 15, I went downtown to the Boulder Bookstore and bought an Anthology of Beat Poets. Founded by David Bolduc, himself an acquaintance of Allen Ginsberg, the Boulder Bookstore was the intellectual crossroads for my own journey of deconstruction and discovering my own authentic spirituality and identity. As I kept following in the footsteps of Huston Smith and the Beats, I became an amateur Zen Buddhist. It was here that I bought my first anthology of Zen koans, puzzling over the refreshing riddles of the Rinzai sect in hopes of having some sort of epiphany. Later, I came back and bought my first collection of Sufi poetry, a little pocket-sized book of poems by Jalal Ad-Din Rumi. I began to fine tune my spiritual compass back towards a theistic mystical practice centered in the Abrahamic faiths I was more familiar with. The Beat anthology contained hits from Ginsberg, as well as many other Beats whose names I had heard and ones I hadn’t. From the spiritual side of things, I was moved by Diane di Prima’s poem “I Fail as a Dharma Teacher,” a poem detailing her own journey of success and failure to practice Buddhism, along with a luminous reflection on the hope of seeing joy and liberation in the midst of a world of sorrow. I imitated this poem, substituting the now Christian and Jewish traditions I had tuned my compass to, with an ekphrastic piece entitled “I fail as an Anabaptist Celtic Abbot”. The Beats had a tendency to seek meaning and liberation from the status quo through a return to textured mysticism and ancient religious traditions, even if their use of those traditions was sometimes problematic. This resourcing of timeless wisdom deeply influenced my ongoing process of religious deconstruction. For a change of pace, I first threw myself into the farthest reaches from Christianity I could think of, mainly Buddhism, certain forms of Hinduism, and neo-paganism. Periodically, I would find books at BB or the library that put these traditions in dialogue with Xtianity. “Zen for Christians” was a short, potent text whose mantra has stuck with me as a reminder of non-duality: “Life is a mess, but it’s ok anyway.”

As I came to understand what it was in my early formation I was rejecting and what it was I wanted to preserve, I homed in on mysticisms, monasticisms and contemplative practices in the Abrahamic faiths. As I began to discover that my faith still lay in some form of relationship to Christ and a mystical practice of Christianity, I did the same hermeneutical and epistemic work that the Beats did, applying it to my own tradition. I studied church history, monasticism, small counter cultural traditions within Christian history and in the present. At age 16, I attempted to start a theology group with some of my youth group friends for mutual prayer, conversation, and sharing of our findings. I gave one talk on “the lost history of Christianity,” centering on the Oriental Orthodox Churches, Anabaptist pacifism and politics. I gave another talk on mysticism in Celtic and Eastern Christianity. After that, word reached an unnamed pastor in our church who pressured our youth group leaders to shut this group down. We continued to meet as a church small group, but the theology club fell apart.

IV. Almost Like the Blues

In 2014, Leonard Cohen, himself a contemporary of the Beats, released his album “Popular Problems.” In the opening track, he growls the following lines:

I saw some people starving

There was murder, there was rape

Their villages were burning

They were trying to escape

I couldn't meet their glances

I was staring at my shoes

It was acid, it was tragic

It was almost like the blues

It was almost like the blues

It occurs to me that the Beats, though an interracial movement, might be the closest that white writers have come to something like the blues. Black liberation theologian James Cone describes the blues as the unique heritage of black resistance and a celebration of life in the midst of the dehumanization caused by white supremacy. He states in no uncertain terms that whites cannot experientially understand the blues, and he is right. Yet if we examine what it might have been like for the white oppressor to begin to reclaim their own humanity, to betray and defect from white hegemony, we might imagine that positive betrayal would sound something like the Beats. A kind of tearing at the fabric of white self-imposed alienation, a celebration of both rage and beauty that the normative social order sought to control and erase. The fact that it was not always perhaps as healthy as the blues shows the effects of whiteness on the psyche of its subjects. There are wounds there, and woundedness sometimes perpetuates itself even as it reaches for healing. The fact remains though that the Beat movement touched certain heights of pathos, authenticity, yearning and resistance. This shows that it truly struck a chord of liberation, a chord which helped spark an entire counterculture. I am speaking highly tentatively here, but it seems to me that there are two roads by which this movement may have been able to begin to break free from white hegemony: those roads are Queer resistance, and productive slippage by communities at the edges of white assimilation.

I will explain the second road first. Some of the founders of the Beat movement were assimilated as white Americans but came from communities that had only been partially assimilated and whose “allegiance” to the fiction of whiteness had been periodically called into question. Jack Kerouac and Gregory Corso were Roman Catholic, and Corso was specifically Italian-American Roman Catholic. Italians and Catholics had been persecuted by the Ku Klux Klan in the 1920s, and had begun to be assimilated by Corso and Kerouac’s time, but one imagines there would still be a sense of being somewhat “outsider” to WASP culture, particularly for Corso as a child of first generation immigrants. Ginsberg, Hettie Jones (nee Cohen) and Lawrence Ferlinghetti were Jewish. Willie Jennings, a black theologian and professor at Yale, has written an extensive meditation on the complex, sometimes fraught but often mutually empowering relationship between black Americans and white Jewish Americans. Jennings’ research on the subject is expounded in his book Christian Imagination, a text about the theological underpinnings of race and racial capitalism. He names the ways that black and Jewish arts have mingled together to form myriad commentaries on identity, belonging and community in the midst of white supremacist alienation. It is beyond the scope of my expertise to trace all of these threads. But Ginsberg, as a prime example, relies heavily on imagery from his Jewish heritage to critique American hegemony and the kind of psychic violence it does on its perpetrators and its victims. Consider the elaborate equation of white American capitalism with the anti-Hebrew deity of child sacrifice, Moloch, in the lines of Ginsberg’s “Howl”. Black members of the Beats were fewer and further between, but those who participated certainly contributed the insight of their lived experience to the ongoing cry of resistance against the post-war American white hegemonic machine. Taken together, these voices brought a context and an awareness that the world of white hegemony was not all that there was, and they began to imagine new paths towards belonging, tangled and fraught though such paths often were.

The other road, queer resistance, was equally energized in the Beat movement, in ways that contemporary queer theorists and activists often struggle to meaningfully categorize and reckon with. William S. Burroughs was perhaps the most unlikely progenitor and forerunner of a movement like the Beats. He came from a fairly wealthy white Protestant American background, went to Harvard University, and even enlisted in the army to fight in WWII (although he was not chosen to serve). Nevertheless, Burroughs’ lived experiences and desires set him on a course to the Beats. Burroughs had many sexual encounters with both men and women, and was open to the point of graphic description about many of these encounters, whether in autobiographical or fictionalized form.

Many years after my initial encounter with the Beats, in my first year of seminary, I picked up a copy of Burroughs’ book, The Wild Boys: A Book of the Dead. The Wild Boys is a stream-of-consciousness novel about young gay guerilla warriors on roller blades taking down a post-apocalyptic dictatorship. Though not quite as scattered as his more famous novel, Naked Lunch, both books share Burroughs’ penchant for graphic descriptions of gay sex with an unabashed literary delight. I would not have been ready for Burrough’s crass beauty during my initial encounter with the Beats, but reading The Wild Boys as an out bisexual man, I found it haunting, moving and luminous. It comes out of a lived experience of the joy of gay sexuality and homoerotic social bonds, a shared experience from which my own life has been greatly enriched. Yet Burroughs had an ambivalent relationship to self-identifying as gay or bisexual. Some of this may be due to the lack of shared queer identity consciousness that would later coalesce around events like the Stonewall riots. Still it’s worth naming that in America at least, many of the sexually ambiguous Beat authors laid the cultural groundwork for queer desire and kinship to be a thing that the art world could express in language openly. Ginsberg, Neal Cassady and Jack Kerouac all had intimate sexual relations with each other, while in many cases also being married to wives. The relative harmony and disharmony of these relationships is complex, but nonetheless they existed. Jamie Russell, a literary journalist, writes that Burroughs inhabited a “gay subjectivity” which has been troubling to queer theorists. While I’ve not read Russell’s work, I can extrapolate what Russell is referring to. In Burroughs in particular and in the Beats more broadly, there is a lack of interest in identifying with a named gay or queer community. Inasmuch as queer theory posits a shared experience and gay activism posits a shared community, the Beats in many ways feel like a disappointment to modern queer thinkers. Living in a time before the full emergence of queer consciousness, they were a small part of laying its foundation. More specifically, their frank and unabashed openness in discussing queerness and sexuality at all in front of a largely white audience began to break open the stranglehold white hegemony held over sexuality, kinship and identity, particularly though not exclusively for white people. Queer writers who could speak openly about their experience turned the stigma and scandal of non-hetero sex and gender into a sword that sliced open the fabric of midcentury capitalist nuclear family values and tore a hole to greater freedom and conscientization of their audience. The downside, however, is that a sword can cut both ways.

V. The Dark Side of the Beats

(TW: Discussion of Sexual Abuse and Pedophilia)

Here seems as good a time as any to acknowledge some of the failings of Beat sexuality. The first failing, though not strictly the fault of either party, was the falling out between the Beats and figures like Amiri Baraka (formerly LeRoi Jones) who were leading parallel traditions of black radicalism and liberation. There is some evidence to suggest that Baraka had some same-sex encounters during his Beat years, but his later writings equated white hegemony with the perceived effeminacy of white queer masculinity, asserting over-against it the pure strength and conscience of black masculinity. While the queer subjectivity of the Beats allowed a great deal of freedom for queer expression eluding censure, it also allowed participants to disavow their kinship with it for other political reasons. It could not be all things to all people.

Another failing was the way in which Beat sexuality also reproduced certain patterns of Orientalism and colonialism. Burroughs, for example, sought out enclaves of more socially liberal sexual practice in places like the Tangier International Zone. Though he spoke fondly and positively of these communities, the experience of a white man entering historically non-white countries for the purposes of sexual tourism still capitulates to fetishizing and the unquestioned white access to non-white bodies, even if the white man in question is queer. One is reminded of the exploits of Lord Byron (a Romantic admired by some Beats). On the one hand, Lord Byron encouraged and supported the Greek liberation movement, and campaigned alongside Greeks for Greek independence from the Ottoman Empire. On the other hand, Lord Byron also expressed his bisexuality through sexual institutions like the hamams, or Turkish baths. These institutions were exoticized and fetishized by white Orientalist outsiders. Furthermore, many of the boys Byron met at the baths were only made available to him because of the subjugation of non-Turkish peoples by the Ottomans insiders, through practices such as the Ottoman slave trade and the paidomazoma, or “child harvesting,” the kidnapping of Balkan Christian boys to serve in Ottoman military and social institutions.

Finally, it is worth naming the most egregious sin of Beat sexuality which, though not shared by all the Beats, was nonetheless unfortunately common: the tendency of advocating pederasty and pedophilia. Ginsberg was a noted member of NAMBLA, and some other Beat and Beat adjacent writers were either members themselves or wrote approvingly of the concept of pederasty. In naming this trend, it is perhaps best to follow feminist writer Andrea Dworkin’s critique of Ginsberg, that

“I did think he was a civil libertarian. But, in fact, he was a pedophile. He did not belong to the North American Man/Boy Love Association out of some mad, abstract conviction that its voice had to be heard. He meant it. I take this from what Allen said directly to me, not from some inference I made. He was exceptionally aggressive about his right to fuck children and his constant pursuit of underage boys”.

Of these faults and of the advocacy for them there is no defense. Though some of the liaisons Beat poets cultivated were legal (if unbalanced in power due to an age gap), they were nonetheless problematic by proximity to the predatory pursuit of youth. Yet it may be helpful to also name that blanket censure of queer sexuality may have created an environment where predatory bad actors (both in and out of the Beats) wielded undue power in the shadows. When the choice of a young queer person struggling to discover themselves is a choice between practicing unsafe sex with someone more powerful or continuing to repress, desperation can lead to concerning outcomes. This, of course, does not excuse the abusers by any means, but it may be instructive to society that abusers will have less room to operate if healthy sexual expression between adult equals is not censured. I was blessed to have been born in a less repressed era, and to have not been put into situations such as these as a teenager still coming to understand my queerness. Being young in a context that, while still far from fully liberated, was far less repressed than the 50s, I did not pick up on the pedophilic undertones in some of the Beats. Had I done so, I have no doubt I would have been as repulsed then as I am now by those undertones. For all the help that the rest of the Beat canon was to my own healthy self-discovery, however, I cannot reject the movement as a whole, as it contains some valuable truth, particularly in relation to queerness. Having acknowledged problems, I will now turn to more of the successes of Beat queer sexuality.

VI. Eros and the Politics of Pathos

There is a deep homosocial-turned-homoerotic current in Burroughs and the Beats which points in an revelatory way to the unhindered possibilities of sexuality, eros, and intimacy. Existing in a time before queer political identity labels, one can almost envision in the Beats a time far from now when we can describe our experiences with terms but no longer need to label them as over-against any other experience because full justice and liberation is achieved. When people can desire whoever they might ethically desire, can experiment, and can inhabit a multiplicity of erotic, sexual and social possibilities without having to commit to any one particular frame of explaining them except their own unique personhood and whatever terms are helpful. As a teenager, I found this gay subjectivity invaluable. Not because it convinced me that I wasn’t queer (although that may have been a thought that crossed my mind early on), but because it allowed me to inhabit through literary worlds of shared affection what it felt like to be gay, bi and queer without having to stake my claim on a label and deal with the repercussions thereof before I was ready. At the same time, the vigor, joy and earnestness of Beat queerness, as I said before, kept me honest. I rejected out of hand the toxic closeted “straight” bro culture (apart from a brief self-repression my first semester of college) because I saw in the Beats and others that whether or not I could accept calling myself queer at the time, my experience of queer desire and the sensual enhancement it brought to my life and friendships were things to be celebrated.

More broadly, I think the Beats taught me much about the politics of pathos. While you can’t build a movement entirely on sentiment, I think many of my fellow leftists (especially young white leftists) are motivated largely by anger and a kind of cynical pragmatism, and are unable to see the transformative power of pathos, vulnerability, affection and delight. Where is our leftist joy? Where is our leftist love? Following Audre Lorde and the early Church, I understand eros as the human drive towards the fullness of life. Though the Beats were often anguished and often angry, their writing speaks profoundly to the power of positive pathos, affection and affectibility to point to new visions of change. This reminds me of a phrase that has floated around Tumblr: “not gay as in ‘happy’, but queer as in ‘I love you.’” The Beats at their best point to what new hope and creative solutions we can find when we are moved by our kinship with one another to seek wholeness and liberation. When Allen Ginsberg writes to Carl Solomon, “I’m with you in Rockland mental institution”, there is a profound identification at pointing towards a love that creates solidarity. The Beats create an affective world which, in a queer way, points to the possibility of life being something other than the totalizing course of white hegemony we see around us. As queer theorist Jose Esteban Munoz suggests, queerness points to a utopic, prophetic “there and then” which disrupts the tyranny of the now by teaching us to yearn and work for something better and more beautiful. The Beats, utilizing both queer and non-queer currents, enact a similar prophetic pointing. The fact that their writing was one force in bringing the work of political radicals to broad cultural attention shows that there is power in pathos, eros, and creative hope. Capitalism and its interweavings with whiteness, cisheteronormativity and patriarchy tell us that we exist to be used. Politically engaged eros tells us that we exist to be and be loved, and that there is power in that love to break our chains.

The Beat of Our Own Drums

Drifting back to spirituality, another trend of the Beats that has been unconsciously and semi-consciously mirrored in my life is the trend of initiation and continuation of ancient religious tradition in a new idiom. Gary Snyder, Allen Ginsberg and others studied under religious leaders in the Buddhist tradition. Though their usage of Eastern religions leaves something to be desired at times, their study and practice was deeply examined and informed by their encounters with living holders of the traditions. In various ways, the Beats and their successors founded offshoot communities to practice Buddhism and other religions in a new American context (cf, for example, Naropa University’s collaborative work between Chogyam Trungpa Rinpoche and the Beats). While they often took these spiritualities in unconventional directions, such diversions were informed by a deep study and encounter with said spiritualities. Their work was also grounded in meditative practice, contemplation, and spiritual retreats with the intent of developing their own personal and communal orthopraxies.

Once I returned to my Christian faith and began to pursue Eastern Orthodoxy, I followed a somewhat similar path. I read many of the Church Fathers and Mothers of the Orthodox Christian tradition, and read commentaries on their work. I participated in a variety of Orthodox liturgies and eventually underwent catechism in the Greek Orthodox Archdiocese of America (GOARCH). For almost four years I did my best to faithfully participate, attend services, pray and grow in my Orthodox faith. My queerness and my calling to ministry eventually made this untenable, but rather than leave entirely I took a page from the Beats and was determined to help construct a new wineskin for the wine of Orthodox faith I had received. Thankfully, I had come into contact with my now-bishop, a woman who underwent even more intensive initiation into the Orthodox faith of her ancestors, an initiation which included time in a Russian monastery. Between her, myself, and my colleagues, we began to build up the Universalist Orthodox Church, a fully LGBTQ affirming Orthodox jurisdiction committed to bringing the best of Orthodox Christian spiritual acumen to bear on the needs of our time, serving Christ, praying and working together, loving our neighbors to the best of our ability and employing the wisdom of the saints across the ages to cut through the oppressions we see around us as faithfully as we can.

Conclusion

It’s hard to know where to conclude this reflection. There’s more I could say, and there’s more that is still unfolding. To sum up, I sincerely hope that this may be illuminating for folks who have deconstructed or are in the process of deconstructing or reconstructing. The Beats are a flawed but powerful example of how sexuality and spirituality can be liberated from oppressive norms in a way that does not necessitate the loss of either. Furthermore, I think the turn to subjectivity, thoughtful examination of our individual and collective past, can help people begin to de-absolutize the problematic beliefs we’ve been raised with (be they religious or social) and to tell new and better stories with our lives. We can learn to break down oppressive walls of bad doctrine and bad social ideology and build new temples of love, belonging and liberation. To paraphrase one of John Green’s videos, the only way out may be through, and the best way through is together, both with one another and with the wisdom of those who have come before. I’ll conclude with some lines from Diane di Prima:

“I Fail as a Dharma Teacher

[...]

Alas this life I can’t be kind and persuasive

[...]

But oh, my lamas, I want to

How I want to!

Just to see your old eyes shine in this Kaliyuga

Stars going out around us like birthday candles

Your Empty Clear Luminous and Unobstructed

Rainbow Bodies

Swimming in and through us all like transparent fish.”